In the last two months of the Biden administration, nearly $500 million in grants were announced to support Tribal broadband projects. From Alaska to Virginia, 55 Tribal nations were poised to improve Internet access and advance digital sovereignty in their communities.

As President Trump took office, more than a hundred applicants still awaited word on their proposals, with nearly $500 million still available in the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program (TBCP).

Then, silence. Ten months of silence.

In early November, Senators Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) sent a letter to NTIA officials asking about the TBCP. The program was established with two appropriations totaling nearly $3 billion. The first round of TBCP grants rolled out throughout 2022 and 2023, totalling nearly $100 million in use and adoption funding and over $1.7 billion in planning or infrastructure funding.

The $500 million announced at the end of the Biden administration was part of round two of the program, for which applications were due in March 2024. With about $1 billion available, only about half of the funding in round two had been allocated.

What was happening, the Senators asked, with the rest of that funding? There were other questions too.

Why were there delays in disbursing announced awards? Did the Trump Administration plan to change the terms of past awards? What technical assistance did NTIA offer round one recipients? Was NTIA using any cost metrics to evaluate prospective projects? How did NTIA plan to untangle any competing efforts to serve Tribal lands through the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment Program (BEAD)?

Though NTIA did not release a direct response to the Senators’ letter publicly, it issued a press release less than a week later announcing “reforms” to the TBCP program. NTIA said it was “not rescinding any obligated awards,” but no new awards from the last batch of applicants would move forward. Instead, the agency would issue a new Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the remaining funds, which would also fold in some funding under the otherwise ”terminated” Digital Equity Act. A new NOFO means a new, different program, with new rules, no earlier than Spring 2026.

While NTIA has offered few details on what changes might actually be coming in the TBCP program, it did appear to successfully shape the narrative around the changes. News sources have largely echoed NTIA’s language in headlines about the program “cutting red tape” and “increasing connectivity.” There are improvements that some Tribal nations would like to see in the program, but in the context of the Trump-era NTIA and with little in the way of specifics, a little more credulity may be warranted.

When the NTIA released a “Dear Tribal Leader” letter last week, it raised more questions than it answered, and only seemed to confirm many of the fears Tribal leaders had about the direction of the program.

Told To Wait, Now Facing a Reset

For Tribal nations who had not yet heard back, the wait was not just frustrating. It was wasteful. After the Nez Perce Tribe submitted its TBCP application, it went back and forth with NTIA answering questions in a process called “curing.” Finally, the Tribe was told that the grant was sitting on the Secretary’s desk for signature – but that was months ago.

Instead, a form email arrived just a few days before the press release. More than 18 months after applications were due, the opportunity was canceled. Melissa King, who runs the Nez Perce Tribe’s Internet Service Provider (ISP), said this waiting game was “inefficient.”

“We need to keep resources engaged on this and doing so for multiple months, if not years, is a complete waste.”

Though the press release was careful if obscurant in its phrasing (“NTIA is not rescinding any obligated awards”), it has been confirmed that NTIA will not be honoring the handful of grants that were announced and approved but not yet through the paperwork. In an echo of hundreds of years of history, the government appears to be walking back its promises.

An anticipated award to Taos Pueblo is one of those canceled grants, and its experience helps illustrate the damage done by this late-in-the-day announcement.

Announced in January, the Pueblo’s award would have built a fiber-to-the-home network to serve over 400 homes on Tribal land in both the central town and in outlying communities. Marc Vaccarino, the Pueblo’s CIO, and Vernon Lujan, Deputy Chief Operations Officer, told ILSR that the announcement came after months of engagement with NTIA in the curing process, substantiating the Pueblo’s data and answering questions.

A pause in the process came with the arrival of the Trump administration, with silence lingering for months. Then a call saying NTIA planned to release the promised funds brought a ray of hope. But, again, the approvals dragged on for another few months. Finally, just a few weeks before the November press release, the final word: nevermind. The project would not be moving forward. Seven other Tribal nations are likely to have the same story.

This lost funding amounts to over $160 million. For those whose awards are “safe,” the press release simply says that obligated funds will not be rescinded. It does not explicitly state that the projects will be permitted to move forward without changes. Tribal broadband advocates say NTIA should make clear that new requirements will not be imposed on existing projects.

Taos Pueblo and Nez Perce Tribe had every reason to believe that funding would be available to transform Internet access for generations. The wait had put a damper on their excitement, stalling progress for no discernible reason. But, they still felt they were on the cusp of something great. Now they were back at the start and should expect to follow a different, unknown set of rules.

Decoding the Buzzwords

Given how little information was included in NTIA’s press release, we are left to read between the lines. For the staff of Tribal nations who spoke to ILSR, the announcement raised fears that NTIA may decrease investment in future-proof technologies, throw up hurdles for Tribal nations still wrestling with bad data, force Tribes to accept subpar solutions through the BEAD program, and weaken Tribal consent requirements. The “Dear Tribal Leader” letter’s leading questions reinforces rather than assuages these concerns. Such changes would turn a once transformational investment into yet another short-term bandaid.

What follows is an examination of the various buzzwords in NTIA’s November 12th press release and December 4th “Dear Tribal Leader.”

“Maximize Tribal Connectivity” and “Stretch Every Dollar:” While “maximize Tribal connectivity” sounds like a worthwhile aim on the surface, some Tribal nations fear this means a rejection of fiber technologies — the gold-standard of Internet connectivity and the only technology that is future-proof. Most of the previous TBCP construction awards have gone to build fiber-to-the-home networks, promising a long-lasting solution to decades of digital neglect.

Melissa King from the Nez Perce Tribe and Marc Vaccarino from Taos Pueblo both expressed concerns that a new-look TBCP would prioritize wireless or satellite options, much like we’ve seen with the BEAD program.

Nez Perce applied to build a fiber network because it would give them “more bang for our buck,” King told ILSR. A wireless deployment could get them six to 10 years of high-quality Internet access, she estimated, whereas fiber was an investment for perhaps a century.

“Cheaper is not better, or long-lasting,” she noted.

For Taos Pueblo, wireless or satellite simply aren’t as appropriate long-term given the Pueblo’s environmental and geographic factors. “That’s not what we need - we need fiber,” Vaccarino said.

The “Dear Tribal Leader” letter likely confirms a new bias against fiber, including two questions (out of eight total) focused specifically on satellite and fixed wireless technologies. One strikes a particularly condescending tone, suggesting that Tribes merely need “additional information on the latest advancements and improvements” in order to feel satisfied with these technologies.

Some Tribal nations have made good use of wireless technologies to bring connectivity to residents, leveraging the resources that were available to them to quickly start closing the digital divide. But NTIA should listen to the careful research and planning done by Tribal nations themselves and not pressure Tribal nations to use a less expensive but shorter-term solution.

“Prevent Duplication:” Another commendable-sounding effort on the surface, this pledge to prevent duplication may once again make Tribes victims of bad data or force acceptance of BEAD plans made without Tribal engagement.

Advocates have long criticized the federal government’s data on Internet access, especially in rural and Tribal areas. Some of these criticisms have been resolved with more granular, location-level maps introduced in the last few years, but others linger. Because of these concerns, the first two rounds of TBCP permitted Tribal nations to self-certify that residents were unserved, though round two required that the Tribe also show proof that it had challenged the status through official data channels.

Even under those conditions, Tribal nations like Taos Pueblo facing inaccurate data had to expend significant energy to substantiate corrections.

If NTIA forecloses even these pathways for data correction and instead shifts the emphasis entirely to the existing federal broadband map, some Tribal nations may be shut out of funding opportunities that could ensure connectivity to unserved households.

The timing of these delays also put Tribes in a real bind with BEAD. While Tribes awaited official word on their TBCP applications, states progressed through planning and into bidding processes for BEAD. Hoping to build a fiber network through TBCP, the Nez Perce Tribe respected rules against duplication and declined to bid on those locations under BEAD. Taos Pueblo, too, announced as an awardee of TBCP, chose to forgo participation in the state’s BEAD bidding process where new rules favored wireless or satellite.

Now, the envisioned TBCP-funded fiber deployments have disappeared. Meanwhile, states were required to “preliminarily award” these locations through BEAD regardless, so another provider has been selected as the recipient of funds. As a result, thousands of locations on Tribal lands risk being stranded with satellite as the only option. In a world full of bad options right now, King laments that they didn’t hear from TBCP “four weeks earlier.” At least then, the Tribe could have bid on BEAD.

The timing of the TBCP cancellation is bad for states too. They were put on a shot clock but operating with incomplete information. ILSR has been told that at least some states were not aware that anticipated Tribal projects would not move forward until NTIA’s press release. Now they must figure out how to fix what never needed to be broken.

ILSR had heard rumors that a new TBCP would cut out infrastructure development altogether and focus exclusively on use and adoption activities. The “Dear Tribal Leader” letter, which celebrates the “progress of the BEAD program” and promises to prevent “duplication” with BEAD, makes this look increasingly likely. There is real danger that the administration will declare BEAD a success and move on from supporting infrastructure in Indian Country altogether.

“Ensure Consistency across NTIA’s Broadband Initiatives:" This could mean any number of things, but one pressing concern is how new rules might affect Tribal consent requirements.

Tribal consent requirements emerged in broadband programs after sustained Tribal advocacy. Tribes and Tribal groups consistently sought such requirements in broadband programs as an exercise of Tribal sovereignty and a pillar of the nation-to-nation relationship between federally-recognized Tribes and the US government.

Many saw the consent requirements in BEAD and TBCP as a step in the right direction. But those protections in BEAD have been eroding, and some Tribal nations worry the same will happen in a new TBCP program.

In August, NTIA issued a “programmatic waiver of Tribal Consent Deadline” for BEAD. Though NTIA continued to affirm BEAD’s Tribal consent requirements, the waiver would allow states a window of six months after the approval of their final plan to submit evidence of consent.

The waiver notes that an award for deployment on Tribal lands would not be dispersed until consent was obtained, but it allowed states to move forward with provisional awards to providers without any evidence of prior Tribal engagement or involvement.

Tribal nations may again be in a situation to consent only after the fact to an infrastructure plan they had no hand in designing. Awardees might be tempted to use pressure to secure consent. Where consent is withheld, the Tribes face more questions about what happens next.

By “speeding” the process along, NTIA has created new logistical challenges that might actually delay meaningful deployment on Tribal lands.

In places where the provisional awardee was SpaceX, as is the case with Nez Perce Tribe and the Pueblo of Taos, these questions seem particularly pressing. NTIA has said that low-Earth orbit satellite providers are bound by the same Tribal consent policies, but fears remain that this could change or that compliance would be harder to monitor.

Both the Nez Perce Tribe and the Pueblo of Taos were unequivocal when asked about the significance of Tribal consent requirements for any future TBCP program. “Non-negotiable,” said King. “The Tribe should be given complete control and sovereignty over any projects that impact their lands, and it should be up front.” Corners should not be cut, even if a new program emphasized wireless or satellite technologies, Vaccarino agreed. “Tribal consent is required.”

“Reduce red tape:” Applying to these broadband programs requires considerable effort, and Tribal nations sometimes complain about the mountains of paperwork they have to complete. One project-planning consultant told Investigate Midwest that applying for a grant entailed coordinating - and paying for - proposal writers, environmental review, engineering and design teams. So, in the big picture, cutting out some red tape is a worthwhile endeavor from the perspective of Tribal nations. But the devil is in the details.

TBCP applications required a number of supplementary documents that might be considered “red tape,” like climate preparedness, cybersecurity, and labor standards plans, a pro forma and detailed plan for long-term sustainability, and environmental and historical preservation reviews.

While challenging and costly to generate, several of the individuals who spoke to ILSR felt that many of these requirements were actually important and useful for long-term project viability. When ILSR sent one consultant the-above list of requirements, they pointed only to the pro forma as a particularly difficult burden for Tribes that did not yet have an operational ISP. A Tribal awardee noted that they anticipated that a climate readiness requirement would almost certainly be axed, but cautioned that building climate resilient networks is actually critical to long-term connectivity.

Tribal applicants have raised complaints about elements of the TBCP program that are onerous or time consuming, but issuing a new NOFO is either unnecessary or insufficient to resolve most of them. Some - like a 2 percent cap on administrative costs - were written into the legislation. Others - such as the tedious and onerous curing processes and reporting requirements - could be changed without a new NOFO, and without throwing away projects already in the pipeline.

And does it make sense to change the rules of the whole program just to “cut red tape,” when applicants had already spent the effort navigating that red tape? Instead of saving Tribal nations time and money, calling a do-over with new rules just as they were at the finish line actually costs them more. Besides staff time, Tribal nations have spent upwards of $500,000 on external partners, planning, and engineering. Now they’ll have to do it again. That’s a lot of red tape to cut if NTIA wants to make this cost effective.

“What types of projects or initiatives – either public or private – have been most effective?:” This is a new question raised in the “Dear Tribal Leader” letter and not in the initial press release, though it will come as little surprise to many observers.

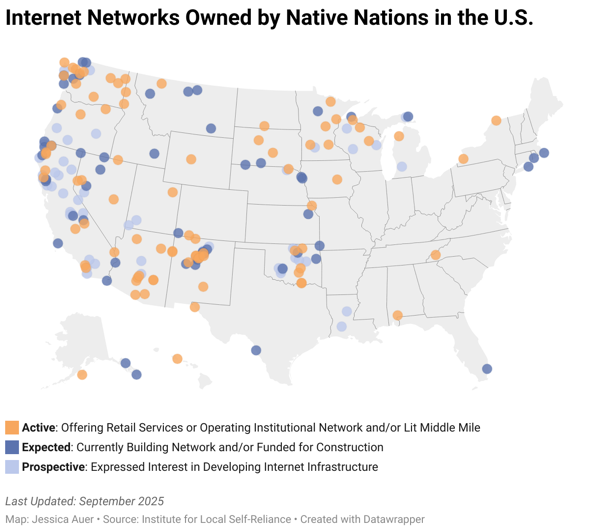

Supporters of public broadband are familiar with efforts to pit private and public efforts against one another. Some Tribes have had great success working with a private provider to bring Internet connectivity to their communities. But given decades of neglect, almost 200 Tribes have taken steps to build their own Internet access as an exercise of sovereignty, with dozens already operating high-quality networks. This was part of the promise of the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program – an opportunity for Tribal nations to put their own economic development, needs, and strategic planning at the center.

This question suggests NTIA would prefer to revert back to the old ways, when Tribal nations were reliant on outside corporations for connectivity, and had little recourse to resolution when so many failed to deliver.

Counting the Cost and Looking Ahead

Taos Pueblo’s broadband journey began in 2020 as the pandemic exposed deep connectivity gaps and pushed the community to use ARPA funds for temporary fixes while planning a long-term solution. After five years of work, what once seemed like a generational investment is suddenly uncertain – and in many ways, they find themselves back at the starting line.

A Tribal consultation will precede the new TBCP funding rules, and Tribal nations are expected to arrive with clear expectations and policy priorities. Whether the program succeeds now depends on NTIA’s willingness to listen. For the moment, what’s certain is that the money, time, and effort Tribes poured into their original applications have been rendered moot, and the process will have to begin again under a new set of rules.

Header image courtesy of Kevin Ku, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Inline image of Sen. Maria Cantwell courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

Inline image of power reset buttons courtesy of Great Beyond on Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

Inline image of Starlink home satellite dish courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons license, CC0 1.0 Universal

Inline image of “status delayed” courtesy of Homes2MoveYou.com, CC BY-NC 4.0, Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

Inline image of government red tape courtesy of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Govt, CC BY-ND 2.0, Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic