Fast, affordable Internet access for all.

In the wake of the new rules issued by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to prevent digital discrimination, digital equity advocates from California to Cleveland are leveraging the new federal rules to spur local action.

In Los Angeles, city leaders have passed an ordinance to combat what advocates say are discriminatory investment and business practices that leave historically marginalized communities without access to affordable high-quality Internet. Similar efforts to mobilize communities and local officials are underway in Oakland and Cleveland.

In November 2023, the FCC codified rules to prevent digital discrimination, outlining a complaint process whereby members of the public can offer evidence of digital discrimination being committed by Internet service providers (ISPs). Though the FCC order does not outline local policy solutions, nor does it empower localities to carry out enforcement of the federal rules, it has the potential to open up conversations between local advocates and elected officials about new ordinances, stronger enforcement of existing ones, or public investment to facilitate competition and the building of better broadband networks.

Los Angeles First City in Nation To Officially Define Digital Discrimination At Local Level

The local organizing work behind the proposed ordinance in LA dates back to 2022 when digital equity advocates began to document inequitable broadband access across the county.

Leading the charge was (and is) Digital Equity Los Angeles (DELA), a cross-sector coalition of LA County organizations founded by the California Community Foundation (CCF) to address broadband inequity during the pandemic. In 2022, the coalition released a report – Slower and More Expensive; Sounding the Alarm: Disparities in Advertised Pricing for Fast, Reliable Broadband – which caught the FCC’s attention and offered an entry point into early discussions with the agency about digital discrimination in Los Angeles.

A year later, DELA hosted an advocacy day convening its members and local officials to raise awareness around the report and to advocate for state policies that would advance digital equity across the state.

When the FCC issued its rules to prevent digital discrimination in November, city leaders seized the moment and worked to craft an ordinance mirroring the federal rules, a process that can result in federal penalties being levied against providers for engaging in discriminatory business practices such as offering inadequate service at a higher cost in historically-marginalized communities – even if that kind of disparate treatment is unintentional.

On Wednesday, the LA ordinance passed with unanimous support from the City Council, making Los Angeles the first city in the nation to define digital discrimination at the local level.

Los Angeles City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson declared his support for the ordinance at a December news conference, framing it as a basic matter of equal opportunity:

“In a city that produces more for the American economy than almost any other region in the country, in a place that is the digital capital of the world, the least we can do is make sure every Angeleno has equitable access to the information superhighway.”

Natalie González, Deputy Director of the Digital Equity Initiative at the California Community Foundation, told ILSR that DELA’s ability to provide research resources for elected officials helped advance the ordinance, made possible thanks to the diversity of its coalition members – a range of community-based organizations focused on housing, immigration, education, civic engagement, social and civic justice.

Although none of the coalition’s members identify as digital equity organizations, González said one common issue they all have in serving their communities is Internet access. In rallying around the need to solve connectivity challenges, it enabled DELA coalition to approach local elected officials – and the FCC – with real stories and a unified voice about the impact of digital discrimination on mostly poor Black and Latino communities in Los Angeles.

“There’s interest in the community,” González said, “and when the community has that coalition, that power-building, and that organizing that we’ve done, [local officials] can’t help but hear us.”

Still, even with a strong local coalition, there is still the ongoing challenge of educating city officials and residents about how, especially in low-income and historically-marginalized neighborhoods, digital discrimination is allowed to occur.

When Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson published the ordinance announcement on social media, comments streamed in from community members who were learning about the issue for the first time.

“With how this [issue] is projected to go,” González said, “there’s going to be a lot of interest from the community to know, ‘Am I being discriminated against?’ ‘Is there anything I can do?’”

That, González noted, illustrates the vital link between public education campaigns and the ability to mobilize communities in pushing for better broadband access.

And while the LA ordinance is hot off the press, it’s already serving as a model for cities in northern California. Digital equity advocates in Oakland and Fresno are looking to the DELA-inspired ordinance as something that could be replicated in their cities.

Shifting ‘Mindset’ Around Digital Discrimination Emerges In Oakland

Just like in Los Angeles, many Oakland-based organizations that rely on Internet access to connect with their clients don’t have the capacity to tackle digital inclusion efforts alone.

Enter #OaklandUndivided – a partnership between the City of Oakland, Oakland Unified School District, Oakland Public Education Fund, TechExchange, and the Oakland Promise. That coalition emerged out of the pandemic to distribute hotspots and devices to students, but is now working to identify more structural solutions to closing the digital divide in the East Bay city, including putting an end to digital discrimination.

#OaklandUndivided Director Patrick Messac told ILSR that in light of the federal rules, it’s critical for localities to “diagnose their own problems” around digital discrimination. He sees the FCC’s rules as a “powerful signal to municipalities to recognize that discrimination does not require malicious actors actively intending to deprive Black and Brown communities of basic resources,” and believes that “the disparate impact framework gives places like Oakland and LA an opening to demonstrate that current practices of the ISPs in our areas are actively harming many of [their] most vulnerable communities.”

Messac thinks cities should be conducting citywide assessments of infrastructure by utilizing community anchor institutions to document disparate impact, which can help local communities get a better grasp of the specific barriers to connectivity they face.

“There is too heavy of a focus on the deficiencies of those who are disconnected,” he said. “It’s not just about digital literacy,” as many ISPs would like local officials to believe. “Until cities demonstrate at scale that these practices are systemic and structural, it’s unlikely that the solutions will match the gravity of the problem.”

It’s a lesson born out of experience. Running speed tests on the equipment #OaklandUndivided distributed at the beginning of the pandemic was eventually used to collect citywide data about the quality of service available in different parts of Oakland. It was a data collection effort that also documented disparate pricing, Internet quality, surprise billing, and harmful collections practices.

It also found that one quarter of AT&T wireline subscribers in the city were receiving speeds less than 25 Megabits per second (Mbps) download and 3 Mbps upload – the bare minimum speed to be considered broadband. And most of those subscribers were overwhelmingly concentrated in low-income communities.

It’s the kind of research that can make a real difference, demonstrating a much greater need for service than what the FCC maps indicated, which, if not corrected, would make it easy for state officials to overlook Oakland’s most underinvested neighborhoods as the state decides where to target broadband investments.

Messac considers the FCC’s new rules as an opportunity for community groups to advocate for better enforcement of existing laws, such as Oakland’s Communications Service Provider Choice Ordinance, which prevents ISPs from monopolizing multi-dwelling units – something Messac says is not robustly enforced.

Still, Messac said, while identifying the data and dynamics involved in digital discrimination is paramount, it doesn’t mean advocates should regard incumbent providers as villains. They can also be a part of the solution. With localities collecting the data that illustrate disparate impacts of broadband investment patterns and practices, the information can be used as a way to nudge large corporate ISPs to connect left-behind neighborhoods, even if only to save face.

But, beyond holding the big incumbents accountable where they must – and partnering where they can – Messac said, what really needs to happen is a shift in mindset. “We need to challenge any mindset where the absence of discrimination is considered charitable,” he said.

“It is not charity to give people what they are paying for. Digital discrimination is not some unfunded mandate for Internet companies, but as a small check on their incredible power over the digital lives of so many within our community.”

Documenting Digital Discrimination The Cleveland Way

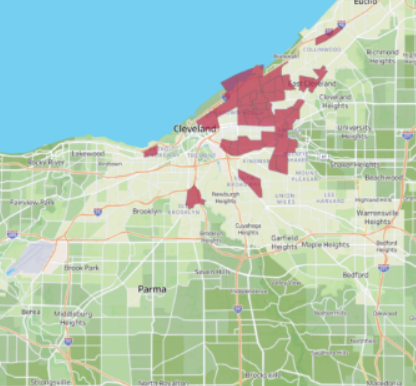

Cleveland is another city where broadband advocates are working to transform the local digital landscape, developing a simple model methodology leveraging the FCC’s new rules and its recently-released location-level data to help communities identify exactly where ISP investment decisions are having a disparate impact.

The groundwork that first laid bare who was being left behind in a city that had come to be regarded as the “worst connected” major metro area in the nation goes back to 2017 and the ascendency of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA) and Connect Your Community, a Cleveland-based nonprofit that works to develop strategies promoting digital inclusion.

Together they published a landmark report “strongly suggest[ing] that AT&T has systematically discriminated against lower-income Cleveland neighborhoods in its deployment of home Internet and video technologies over the past decade.” The report was the first of its kind to wage a major attack on an incumbent provider’s discriminatory practices, using FCC Form 477 Census block data to document the company’s neglected infrastructure upgrades in most high-poverty neighborhoods in Cleveland.

A soon-to-be-released refresh of the report will document AT&T’s discriminatory impact and can be used as a tool or guide for other communities to help pinpoint where digital discrimination may be occurring in their city, Callahan said. The key, he said, is to zero in on the FCC’s new location-level data, which provides a more accurate sense of where underinvestment persists.

“The advantage of the [FCC’s new] mapping data is that it’s current,” said Bill Callahan, Director of Connect Your Community and one of the champions behind the report. “You can see where incumbents have been putting fiber in the last year.” Using the data to document digital discrimination in communities is accessible to anybody who can use Excel, Callahan added. “The question is then about the story you’re trying to tell – a story that is accurate for your area and supports the strategy you’re trying to carry out.”

Beyond data collection, Callahan also sees another silver lining in the FCC’s new rules that cities can use: the informal complaint process.

Callahan said that because the complaint process is informal, it lowers the barrier for cities to submit digital discrimination evidence to the agency. Though some say the FCC new rules lack transparency under such an informal process because complaints aren’t made public, the adoption of an informal process means that cities won’t have to enter into formal litigation processes against incumbents. That’s a plus, Callahan points out, considering that many cities and community groups simply don’t have the resources to conduct the kind of formal analysis that a lawsuit might require, nor are they necessarily inclined to wage public attacks against powerful companies.

No Magic Bullets

While it is uncertain how, or if, the FCC will enforce its new rules to prevent digital discrimination (or if the FCC order will survive court challenges), a vision for how local advocacy can leverage the rules to move the needle is beginning to emerge.

The Cleveland model worked even before the FCC rules had been established as it helped make the case for AT&T to make needed investments in network upgrades, underscoring Messac’s point about including incumbents in conversations about closing the digital divide.

While the updated report documents persistent disparate underinvestment on the part of AT&T, it also shows areas where the company has actually invested in fiber upgrades in the past few years – likely, in part, because of Callahan’s report and Cleveland’s mobilization around the issue.

Still, there are no magic bullets or solutions to fix everything at once. While AT&T has made some infrastructure improvements in Cleveland, the company also has existing easements that give it exclusive rights to the poles in underserved parts of the city. Such an arrangement gives AT&T the power to block neighborhoods from getting access to high-quality broadband outside of AT&T because it limits competitors from attaching equipment to their poles.

Thankfully, city leaders in Cleveland are no longer just hoping AT&T will offer high-quality affordable Internet access citywide. Last year, city councilors awarded DigitalC $20 million of the city’s Rescue Plan funds to build a citywide wireless network that offers subscribers a symmetrical 100 Mbps connection for $18/month.

What is emerging in places like Cleveland, Oakland, and Los Angeles are digital inclusion strategies that use a variety of tools and tactics to challenge the business-as-usual practices of incumbent providers, while still regarding them as key players (somewhat) responsive to digital discrimination data collected and compiled by local coalitions working with elected leaders.

The work can be challenging but the stakes are worth it. “This is the digital civil rights equivalent,” said DigitalC CEO Joshua Edmonds in his Building For Digital Equity keynote on Cleveland’s strides towards universal connectivity.

The sentiment is echoed by campaign posters at news conferences and rallies across California: "Internet access is a 21st century civil right."

Or as Edmonds put it: “We are lying to ourselves if we are not going to give this moment that level of significance. For those who have been on the fence, now is the time to get engaged.”