As Vermont’s nascent Communication Union Districts (CUD) push to bring universal, truly high-speed Internet connectivity to the more rural parts of the Green Mountain State, CUD leaders are calling for changes in how federal funds get funneled to local municipalities, and for a change in how the federal government defines “high-speed” access.

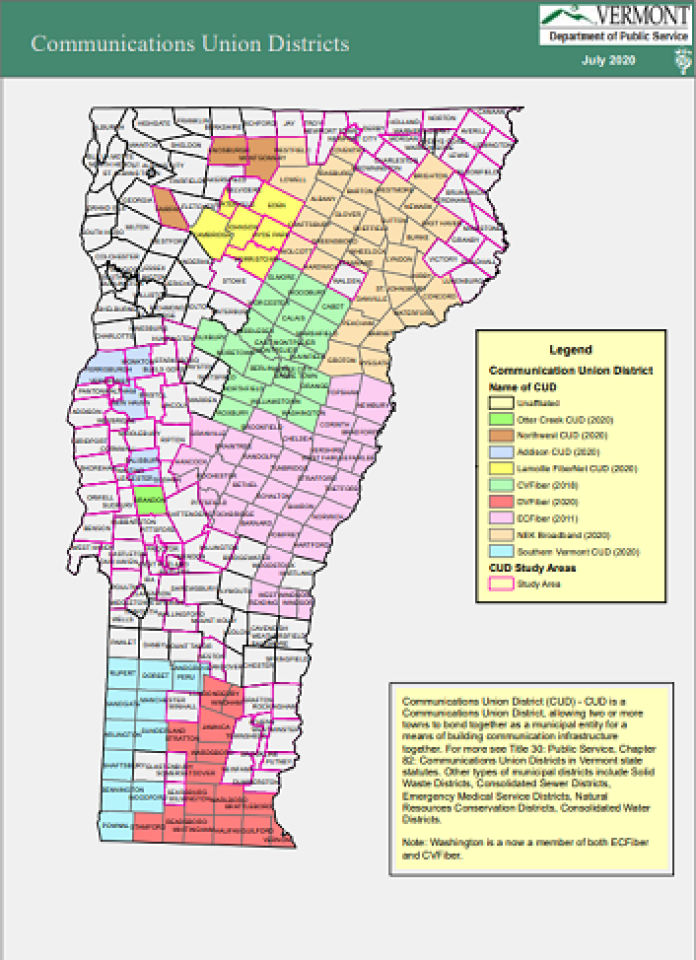

Enabled by a 2015 Vermont law that allows two or more towns to join together as a municipal entity to build communication infrastructure, these local governmental bodies were formed to help the state reach its goal of having universal access to broadband by 2024. The idea is for CUD’s to operate like a water, sewer, or school district as a way for local communities to build their own broadband infrastructure. Establishing a CUD also puts rural regions of Vermont in a position to borrow money on the municipal bond market and eases access to grants and loans to fund broadband projects.

The formation of Communication Union Districts across the state began to pick up steam in the months following Gov. Phil Scott’s signing of H.513 in June of 2019. That legislation, which set aside $1.5 million to support broadband projects, increased funding to help provide Internet service in unserved or underserved parts of the state. It also created a new Broadband Expansion Loan Program within the Vermont Economic Development Authority (VEDA) to assist start-up broadband providers in developing community-based solutions.

Funding Gaps

In a Zoom call last month with U.S. Rep Peter Welch, D-Vt., leaders from the state’s nine CUD’s met virtually with Welch to update the congressman on the status of their efforts and what they see as crucial to succeed in fulfilling their mission without burdening taxpayers.

Representing the Deerfield Valley Communications Union District, Ann Manwaring told Congressman Welch: “It’s wonderful to think about the notion that we should be running like an electric utility. But until there’s some federal legislative action that permits that to happen . . . we have to function much more like a profit-making business without any profits below the line.”

F.X. Flinn, Executive Committee Chair of ECFiber (one of the first two CUD’s to form in east-central Vermont) told Congressmen Welch that in order to reach the state’s goal of providing universal broadband access by 2024, the districts would need to build 25% of their networks by next year at a cost of about $75 million.

“I think the only way that can happen is if there’s a federal infrastructure bill that has money for broadband, where money can be granted directly to the CUDs, and the only barrier that should exist is whether or not they are existing municipalities. There shouldn’t be any other test,” Flinn said during the meeting.

Tim Scoggins, board chair for the Southern Vermont Communications Union District, added that CUDs are made up of volunteers and have no authority to levy taxes. “So professional help would be at the top of my ask,” he told Welch.

Scoggins observation is something touched on by Central Vermont Telecommunications District’s Irv Thomae in his written testimony to the state’s House Energy & Technology Committee in February of 2019:

Because a CUD is a municipal body, once it achieves positive cash flow and a track record of steady growth, it can credibly offer its revenue bonds through the municipal bond market. The more daunting questions for a CUD or any other community broadband project are, of course, not only how to finance initial planning, design, and construction, but also how to subsidize operations in that startup stage.

The emergent CUD’s are also confirming first-hand something broadband experts have been pointing out for several years now. The federal government’s definition of 25 Megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads for “broadband” does not match contemporary needs. Areas believed to have 25/3 Mbps service already do not qualify for most broadband subsidy programs, though most agree that the FCC has poor data on whether that level of service definitively exists in any given region. Most broadband subsidy programs require delivering a new service that is at least that fast, though some have higher standards to ensure government subsidies are not building obsolete networks.

But, as Michael Rooney, chair of the Lamoille FiberNet Communications Union District, told Welch, “what it is currently is this almost useless standard of 25/3, which does not satisfy the needs of even one person.”

Rooney suggested the standard be set at 100 Mbps symmetrical for both download and upload speeds.