A new report by the Electronic Frontier Foundation argues that the general lack of fiber network coverage across the United States - with barely a third of homes able to choose a fiber option - comes in large part from the domination of the broadband marketplace by incumbent providers who both own and operate the infrastructure that provides Internet access to the vast majority of Americans. It’s a classic market failure, authors Benoît Felten and Thomas Langer argue, where there’s a clear profitable business case for the existence of more fiber access that continues to go unaddressed. At its core, the failure is driven by the attitudes of monopoly Internet Service Providers (ISP) which prefer to reap the profits from existing legacy copper and cable infrastructure rather than invest in new build outs. As a result, a larger proportion of Americans than many other nations remain stuck on slower, more expensive connections.

The solution, the report shows, is relatively straightforward and economically viable for as many as 78 percent of all households across the country: the construction of a series of local or regional fiber networks operated on a wholesale basis, whereby any ISP that wants to can join an open, transparent marketplace, creating much more competition than exists in the current arena.

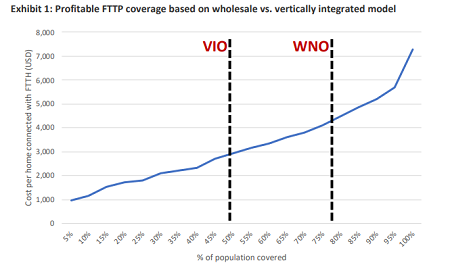

“Wholesale Fiber is the Key to Broad US FTTP Coverage” offers an economic case for open access fiber in improving access, affordability, and driving competition. Comparing the potential of what it calls a Vertically Integrated Operators deployment (i.e. traditional incumbent broadband providers that build, own, and operate networks for end users) and Wholesale Network Operators deployment (an open access arrangement where the physical infrastructure is owned by one entity that invites providers to operate on the network and connect end users for a fee), the report finds that the Wholesale Network Operator model reduces the risk of capital investment, drives infrastructure expansion, and would lead to future-proof connectivity for hundreds of millions of Americans.

- Reducing the risk of fiber infrastructure deployment is one of the most effective ways to increase the potential for private coverage and therefore decrease the need for public funding to bridge the “gap”. However, there are few proven ways to radically decrease that risk in the current market structure. Initiatives to do so end up compromising either market competition, long-term infrastructure or both, and still cost significant amounts of public money

- Expecting private telecom players operating on purely commercial terms in the retail market to invest in nation-building is at best misguided.

- Our analysis shows that a WNO [Wholesale] based model could cover close to 80% of US households with fiber to the premises whereas a VIO [Vertical] model could only reach 50% profitably

Interestingly, the report also suggests that there are hard limits on the number of households that the current VIO-dominated marketplace arrangement is likely to hit with fiber, arguing that the “model could only reach 50 percent profitably.” It further argues that “in our model as it stands, the level of [public] subsidy would have to be, on average, $600 per additional active subscriber to ‘push’ the VIO model towards the performance of the WNO model” in terms of the number of households reached by fiber.

Underpinning the report’s conclusion that the WNO model offers a more efficient route to larger ftth coverage across the country is something called the lower weighted average cost of capital (WACC). At the most basic level, separating the infrastructure layer of the Internet from the service layer is the key, since “investment profitability is directly dependent on the perceived WACC . . . as an evaluation metric for investment viability.” In other words, the safer a bet the market sees fiber to be, the more fiber will get built.

When private companies build a network, they often have a higher cost of capital because they tend to be borrowing from investors that are seeking a fast return on their investment. That puts pressure on business models to build only in areas with the highest perceived demand and ability to pay. But longer term investors - so-called “patient capital” - are more willing to invest in fiber networks today and they seek a longer, more predictable return on their capital. They charge a lower interest rate on borrowing but need to minimize risk to that long term investment return.

The argument here -and it’s a compelling one - is that pure infrastructure in the form of an open access network is a safer investment, at least as the market perceives it, than a vertically integrated model. Over a period of 20 years, if someone builds a fiber network – especially if it is the first one in an area – even if the business struggles in the first 5 years, some entity will be using and paying for that fiber throughout the term. And the level of security is demonstrated by the WACC, which the report finds for the VIO model to be around 5.5 percent, while the WNO model sits at 4 percent.

If this feels counterintuitive, consider it the antithesis of the common narrative we are taught in school when learning about the Industrial Revolution, where oil and railroad and steel companies “discovered” that vertical integration led to more efficient production and ability to scale. When it comes to basic infrastructure, the dynamics differ from competitive markets. And when it comes to broadband infrastructure, the current model (pushed by monopoly providers like AT&T, Charter Spectrum, and Comcast Xfinity as the only path to efficiency and innovation) is in actuality only more efficient at concentrating the profits in the hands of a few actors, thereby stifling investment and innovation.

The benefits of an open access fiber-to-the-home network owned at the local level are many. There are plenty of communities willing to build, own, and operate a network to improve Internet access at the local level, ensuring a future where broadband access isn’t solely driven by short-term profit maximization schemes. But many other communities are not. The good news is that an open access network turns broadband infrastructure into basic infrastructure: something cities have proven successful at building and maintaining for the last hundred and twenty years.

Further, open access networks spur competition by lowering the barrier to entry for new providers, which drives lower prices for residents and businesses and drives economic development. And a well-run open access network can improve the experience for all end users by making it easy to switch from one provider to another, driving up customer experiences. Read more about open access here, and watch the Connect This! Show episode below on the promises, particularities, and challenges of the model.

Importantly, the report shows that the WNO deployment model works within the current broadband marketplace as it stands today, and while it may initially be directed at the less-densely settled parts of the country it is viable for an area even as populous as Los Angeles County.

On the whole the EFF makes compelling arguments, but there are a couple of underlying assumptions in the report that could influence the penetration and success of such an open access fiber network.

First, the report assumes a 50 percent take rate on the wholesale network, which is historically a little high for open access fiber in early years when facing telephone and cable incumbents. The largest open access networks in the country presently - UTOPIA Fiber and the various public utility districts in Washington State - do see penetration numbers that high in areas, but not universally across their footprints. Time, as the report points out, is a contributing factor, but at the end of the day the report shows that the WACC [cost of capital] serves as a larger influence than take rate on the viability of the model as a whole.

Second, the report argues that one of the light-touch regulatory policies which would help drive healthy open access networks is statewide “price equivalency” - what we call price regulation - so that end users have transparency into and less variability within a region. We think it is unlikely that any type of national price regulation will materialize in the near future, although requiring uniform pricing (making it more difficult for monopoly ISPs to engage in predatory pricing in some neighborhoods) in a given market could be a strongly pro-market regulation.

The report ends by offering a list of the other challenges facing the implementation of this model, including mapping, middle mile access, pole and conduit access, the regulatory landscape, and affordability of access and devices.

Read the full report here [pdf].