Representing 26 towns across Massachusetts, from Cape Cod to Chelsea, an informal group of mostly town officials have formed the Massachusetts Broadband Coalition in search of a way out of a broken broadband market to ensure everyone in their individual communities has access to high-speed Internet.

The newly-formed coalition has recently started to meet monthly to share information about what kind of alternatives there might be, or could be, to the big cable monopoly provider in their towns.

Questioning Monopoly Rules Without Reinventing the Wheel

The coalition, which held its first meeting in January, was convened by Robert Espindola, Fairhaven Selectmen and the board’s liaison to the town’s broadband study committee. And though the coalition is “in its infant stages,” as Espindola recently shared with ILSR, one common theme has emerged from each participating member.

“No doubt the common theme is: there’s no competition,” he said. “That’s how it started in Fairhaven for us. When we were negotiating our (franchise) agreement with Comcast, people in the community were asking: ‘why can’t we get competition?’”

When we first came together it was really more just to learn from each other, what each community was doing. And we wanted to see if we could find ways to work more efficiently and not reinvent the wheel.

Indeed, communities across the nation have set out to tackle local connectivity challenges head-on with a community broadband approach without having to reinvent the wheel. Some have built, or are building locally-controlled, publicly-owned open-access fiber networks to create the conditions for competition. Other cities and towns are building, maintaining, and operating their own successful municipal broadband networks. While still others have opted to enter into a public-private partnership with an independent ISP to build out a community-wide network.

Public-Private Partnerships Come into Focus

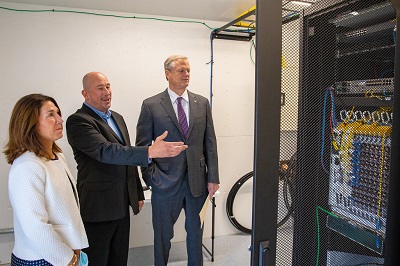

In Massachusetts, on the other side of the state from most towns in the coalition, the state began investing in fiber infrastructure in the Berkshires going back to the former Gov. Deval Patrick administration. New infrastructure money continued to be funneled into western Massachusetts during the Gov. Charlie Baker administration as well.

With those investments, and a strong partnership with Westfield Gas & Electric’s subsidiary Whip City Fiber, today many of those hill towns in western Massachusetts that were once stuck with DSL-only connectivity now have fiber-to-the-home service, just as reliable, but less expensive than similar service in Boston.

Now communities in other parts of the state that are considered technically “served” by an incumbent provider are looking for ubiquitous, reliable connectivity, and more affordable prices.

With the federal government making an historic once-in-a-generation investment to deploy new or expanded broadband infrastructure through American Rescue Plan Act funds and the forthcoming dollars each state will receive from the BEAD program, towns like where Espindola lives in Fairhaven – as well as several gateway cities like New Bedford and Taunton – are looking to possibly tap those funds through a state grant program.

However, as Espindola and others in the group are now seeing come into view, the reality is that Massachusetts won’t likely get hundreds of millions of dollars from the BEAD program, as other larger or less well-connected states are poised to get.

One independent estimate says Massachusetts should expect to get somewhere in the neighborhood of $173 million in federal BEAD funds, or not much more than the near minimum allocation ($100 million) each state will get under the infrastructure bill appropriation rules. (States get additional BEAD funds based on a formula that includes the number of unserved and underserved locations in each state according to the FCC’s flawed maps).

“There’s a sense that there probably won’t be a lot of BEAD funding, and most of the (state’s) funding is for digital equity programs,” Espindola said.

And it’s not just that Massachusetts will likely get the near minimum in BEAD funds. Congress crafted the spending rules such that BEAD funds must first be used to connect areas that are “unserved” by a provider capable of delivering more than the FCC’s minimum broadband connection speed of 25 Megabits per second download/3 Mbps upload. There are few, if any, areas outside of the most rural enclaves in the state who would meet that definition of “unserved.”

BEAD does allow for states to use the funds to build networks in “underserved” areas – households without access to 120/20 Mbps service – but only after the state certifies all “unserved” areas have been served first.

In October 2022, Massachusetts was awarded $145 million in Coronavirus Capital Projects Funds (CPF) from the American Rescue Plan to help fund new broadband infrastructure in the state through a program known as the Broadband Infrastructure Gap Networks Grant Program. State officials said at the time that would be enough to connect 16,000 households and businesses, mostly in western and central Massachusetts, or 27 percent of locations in the state that lack high-speed Internet access.

Given the uncertainty of how much, if any, BEAD funds communities like Fairhaven, Falmouth, New Bedford, Dartmouth and Westport may be able tap, coalition members have recently turned their attention to learning about public-private partnerships in which municipalities build broadband infrastructure in partnership with a private independent provider who can also provide the retail service, give the town a say in the rate structure, and put in place a revenue-sharing agreement.

“Several coalition communities have expressed interest in working together to study the NTIA model for how to form a public-private partnership, with the goal of driving economies of scale to a point where building a shared, open access network would be feasible,” Espindola wrote in a recent edition of the Massachusetts Municipal Association newsletter.

Communities at the Connectivity Crossroads

In Fairhaven, several years ago, the town put out a Request for Proposals seeking competition for the sole ISP in town.

“Our attorney told us: ‘Don’t hold your breath. Unless you have the infrastructure built out, it’s hard for a provider to come in to compete with an incumbent. He was right,” Espindola said, noting that the town didn’t get any response to the RFP.

In 2020, as part of the town’s negotiation with Comcast, Fairhaven officials negotiated a capital fee to which, when matched with town funds, helped the town build a municipal fiber loop to serve as the town’s institutional network.

Espindola said the town is now studying the feasibility of leveraging that loop as a fiber backbone that could be used to extend the network to provide residential fiber connectivity as the existing loop “covers a good portion of town.”

To start, “we could tap into the existing loop to run fiber to the housing authority properties and maybe build off of that for a pilot project for other residential properties down the road,” Espindola said, adding that the plan is to move forward with deploying fiber to the town’s housing authority properties in September using a $250,000 grant from the state’s Municipal Fiber Grant Program and to demonstrate the way an open access network can allow for competitive service from multiple ISP’s.

As for building out a town-wide community network, Espindola said, the big telecommunication questions Fairhaven faces right now is whether the town should create a Municipal Light Plant (MLP) for the formation of a telecommunications utility (as Falmouth and Taunton have done), build a municipal fiber-to-the-home network (as Taunton via its TMLP utility is in the process of building out) or work with other local communities to form a public-private partnership.

“We are trying to figure out the best model for us,” he said. “In Fairhaven, connectivity is fairly high. But people are frustrated with the cost and service – with cost being the biggest factor.”

*ILSR CBN reporter and editor Sean Gonsalves is a FalmouthNet advisory board member

Header image of handshake courtesy of Flickr user franchiseopportunities.com, Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Inline image of Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker looking at installation of the municipal network in Becket, MA, courtesy of Joshua Qualls/Governor’s Press Office, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Inline image of downtown Fairhaven courtesy of Massachusetts Office Of Travel & Tourism on Flickr, Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0)