*This is the first installment of an occasional profile on Local Community Broadband Champions where we focus not so much on the technology, construction, and financing of a community network build, but on the personalities of the people who make it happen.

When Devin Weaver isn’t vibing at the Otto Bar or checking out the underground music scene at Metro Gallery, or even playing his bass guitar at home, the 28-year-old network engineer enjoys spending time amid the web of wires in storage closets inside low- and mixed-income apartment buildings dotting the city’s landscape.

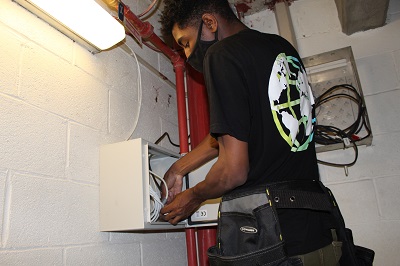

It’s where his network design handiwork all comes together, snaking through the buildings to the routers installed in individual apartment dwellings, enabling residents to get gig speed Internet service.

That’s on par with what the regional monopoly provider Comcast offers city residents who can afford it. But in the buildings that Devin has made his technical playground, hundreds of financially-strapped households who subscribe to the fledgling community network he oversees get it for free – thanks to the philanthropy of dozens of organizations including the Internet Society Foundation, the France-Merrick Foundation, and the Digital Harbor Foundation.

Born and raised in Baltimore, Devin works for Project Waves, a non-profit organization founded in 2018 by an old high school classmate of his, Adam Bouhmad, to bring broadband to mostly low-income households in Baltimore City.

A Small, Rising Wave of Connectivity

With more than 96,000 of Baltimore’s 237,000 residents without a home Internet connection, the city has one of the highest rates of digital disconnectivity in the nation. And while Bouhmad has since stepped away from leading the organization, having turned the reins over to its current Director Samantha Musgrave, it is still guided by the founding vision that “everyone deserves unrestricted access to the Internet.”

The vision was compelling enough to persuade the Digital Harbor Foundation to make Project Waves one of its fiscally-sponsored programs dedicated to closing the digital divide in the city of Baltimore and beyond.

The Foundation lent Project Waves its financial services and development teams to get the project up and running; and, just as importantly, allowed its non-profit status to be used by Project Waves to pursue grant funding.

Project Waves really took off when it stood up a wireless network in 2018 – made possible by the generous in-kind contribution of the Baltimore-based cloud computing and telephony services company LiteCloud who ran fiber to the Exelon Tower to beam wireless signals into the Lakeland, Highland Town, and Cherry Hill neighborhoods. That was done in partnership with Baltimore City Public Schools who allowed Project Waves to put receiver antennas on school roof tops.

Since then, Project Waves has grown from offering free wireless Internet access and public Wi-Fi to now providing far more reliable wireline connectivity to five different apartment complexes across the city. In fact, the growth of the organization’s work convinced the Digital Harbor Foundation to elevate Project Waves from a fiscally-sponsored program to its own division within the Foundation.

‘Meat and Potatoes’

Today, Project Waves serves close to 1,000 households, the bulk of which live in low and mixed-income multi-dwelling units (MDUs) – the Johnson Square Apartments, Chase House, Hollins House, Paca House, and the Ashland Commons. The network serving those buildings is Devin’s baby.

When he first joined Project Waves in the spring of 2021 as a network engineer, and later promoted to Director of Engineering, Devin said initially they were offering only wireless connectivity. But, given line-of-sight issues and other technical limitations of the network, Devin told ILSR “it wasn’t really anything special. There was no licensed spectrum, just 5 Gigahertz stuff.”

That changed when Devin designed a new network for the apartment complexes. “Before, there was so much variation in bandwidth and reliability.” But, with Project Waves foray into serving MDUs, they were able to run fiber to each building and re-use the building’s existing coaxial cable wiring to bring gig speed service to tenants.

“It’s now entirely HFC (Hybrid Fiber Coaxial). Using wireline technology gives us way more consistency,” Devin explained.

Delivering high-quality wireless Internet access often requires spectrum that is not available to local organizations. There are technologies that may deliver a signal but it may not be high-quality, lacking both reliability and decent bandwidth. Project Waves uses coaxial cable that is already in the apartment buildings to distribute the signal within the building. They get Internet access to the building via a fiber optic line, but could also use a high-capacity point-to-point wireless links to go from rooftop to rooftop as some companies do like NetBlazr in Boston.

Operating the network has not been without its challenges but it’s a real labor of love for Devin.

“Honestly,” he said, “the network is pretty small and because it’s small, and stable, there’s not a ton of challenges from a technical perspective. On the deployment and build-side, it’s more challenging. These buildings are so old and were not built with communications in mind. There’s splitter boxes distributed all over the building and also getting through the city permitting process is a lot.”

When the CBN team visited a building Project Waves serves, we saw how the cables for a residential unit could be in confusing places that were not documented, requiring a treasure hunt to find a cable to be able to bring service to a resident.

And while Devin is well-versed in all the technical lingo of the trade, he describes what he does in plain terms.

“A lot of what I do is make decisions on how we do what we do,” he said. “That involves going out to the buildings and doing site surveys and determining what technology will be used. I do a lot of R&D (research and development). I also spend time staying in communication with our fiber (backhaul) providers as well as managing a team of technicians that do the installs and maintenance. But I’m still out in the field and actually really enjoy it.”

Or, as Project Waves Director Samantha Musgrave describes Devin, “he’s the meat and potatoes of what we do.”

A Digital Equity Advocate is Formed

It was Adam Bouhmad, who Devin went to Eastern Technical High School with in nearby Essex, Maryland, that initially encouraged Devin to join Project Waves. But, it wasn’t cronyism that landed him the job. Devin has some serious technical chops.

In high school, Devin was really interested in digital art, music, and entertainment. It was his mother and brother who convinced him to go into IT studies at the magnet school as a more practical pursuit.

“At first I wasn’t really into it. But then I took this one class and learned about TCP/IP and was like: what is this?! I was hooked ever since and got really good at it.”

So good in fact, when he graduated in 2013 he was given the Maryland Blue Ribbon Career and Technology Award for graduating at the top of his class.

After graduation, he enrolled at the Community College of Baltimore County (CCBC), majoring in applied science in network technology, though he didn’t stay for long as he got restless in class. “I just wanted to get started.”

So he enrolled in Cisco’s Certified Entry Networking Technician (CCENT) program, earning his technician level certification in configuration, administration, and management of network devices later that year. A few months later he was hired by the Pittsburgh-based data center cloud provider Expedient where he worked in tech support and quickly completed the Cisco Certified Network Associate (CCNA) program.

“Being in an environment like a data center, it’s so cut-throat. But you learn a lot – if you apply yourself,” he said. “But that wasn’t where I wanted to settle. I had my eye on being a network engineer.”

That opportunity came in early 2016 when a position opened up in Expedient’s network architecture department. The application process was rigorous but Devin passed with flying colors. And for the next five years he managed Expedient data centers where he got real familiar with “zippy switches and modular routers.”

He began traveling for the company where he got to see first-hand a variety of Internet infrastructure, including an inside look of the Pittsburgh Internet Exchange, part of the nation’s Internet backbone that routes Internet traffic between major cities much like the federal highway system serves to transport truckloads of commerce to wholesale markets.

It was an experience that led him to ask a question: Why not in Baltimore? There was no Internet Exchange Point in the city he was born and raised in and had come to love. “Comcast dominates. They have a giant national network so they don’t really need to peer with anyone. So I decided I wanted to build an Internet Exchange in Baltimore."

I didn’t know it was called digital equity at the time, but I realized Baltimore was missing a lot and wanted my city to have these things.

All the while, his high school classmate Adam Bumoud was trying to get Project Waves off the ground. Because they remained friends and shared a common interest, Devin would help Adam test out antennas that would support wireless Internet access in several neighborhoods that weren’t well connected.

“We really cared about this stuff, going all the way back to high school,” Devin said. “And when the Internet Exchange I was working on fizzled out and I realized that Adam and I were really trying to tackle the same issue – lack of infrastructure and lack of competition – we decided to join forces.”

A Model for Other Cities?

Bumoud needed to take a break. But Devin was really hitting his stride and not long after coming to Project Waves to work as a network engineer, he was promoted to Director of Engineering.

Project Waves Director Samantha Musgrave said Devin came to the organization at the right time.

“Pre-Covid we were really talking about the digital divide in rural America. But then Covid hit and it magnified the disconnected, and under-connected, in urban communities. And in urban areas it’s much more about affordability,” she said.

Though most urban centers are served by large private networks, they are typically run by monopoly providers who cherry-pick the more affluent neighborhoods to serve.

“When we talk about digital equity and you only have one (Internet service) provider, they are really only going where they think it is profitable and only going into these (low-income) neighborhoods where they can see (Affordable Connectivity Program) ACP customers turning into long term cable customers,” Musgrave said.

But where the big monopoly providers don’t see enough return on investment for its shareholders, nonprofits like Project Waves see opportunity.

“At this point, we are really dialed into the MDU model,” Musgrave explained. “The low hanging fruit is in low income housing … So we are honed in on delivering the infrastructure and working with housing authorities, which are a huge piece of this. They will play a huge role in closing the digital divide. In Baltimore City, 21 percent of disconnected households live in apartment buildings. If we can deliver fiber to those buildings and expand quality of service, we can then expand into surrounding communities.”

To get where they are now, Project Waves was helped tremendously by a $3.1 million grant from the state’s broadband office, half of which was used to deploy fiber to the premises they serve.

Musgrave thinks Project Waves is a model other cities can learn from.

With the affordable housing community we are leveraging existing cable wiring in those properties to deliver gig speed service at no cost to residents. Of course, we run across developers who say we don’t want to do a retro fit. But, we are not requiring that. All we need is a server room and closet and we can deliver gig speed service. It can be a model for other cities because it’s so simple.

Combine that with the ACP, and Musgrave says it provides a “playbook” to tap into federal funding for the users who need it. The challenge then becomes for city leaders and housing officials to proactively do things like provide the certification documents for their tenants to qualify for the ACP benefit, which would help sustain network operations.

Musgrave is also quick to point out that once they built the infrastructure, their average cost per month to keep the network up and running with customer service support built-in is only $16 per user.

Moving forward, as federal BEAD funds make their way to state grant programs this summer, Musgrave hopes to get middle mile networks to work with last-mile providers like Project Waves.

“If you are building 400 miles of fiber and putting seven or ten thousand strands of fiber in the ground, Project Waves only needs two of those strands. And that can be written off as a charitable contribution,” she said.

Also, she is eager to work with utility service providers who understand the benefit in building out fiber networks and making sure their customers have access to it because “when fiber is more widely available, customers sign up for auto pay.”

Making bigger and better waves won’t be easy but well worth it, Musgrave said. Devin agrees, even as he enjoys riding the wave they are on now.

“I get a lot of enjoyment out of the work,” Devin said. “And what’s most rewarding is seeing the finished product and being like: ‘we did this.’ People are genuinely so appreciative and happy we are doing this. I didn’t really know how much of a privilege the Internet was until I started seeing and hearing from people in these units. A lot of them were getting Internet access for the first time. I remember one guy who was so happy he could video chat with his kids he started crying. This stuff is emotional.”

Musgrave sees the potential for lots more teary-eyed people who can benefit from high-speed Internet service in Baltimore and other cities. And while it takes a collaborative effort to meet the challenge, you need your “meat and potatoes” champions like Devin to get the job done.

Header and inline images courtesy of Project Waves