Four times a week, from 1960 to 1968, a plane marked with the insignia of the Midwest Program on Airborne Television Instruction (MPATI) took off from the Purdue University Airport in West Lafayette, Indiana and flew a figure-eight pattern above Montpelier. At an altitude of 23,000 feet, the DC-6AB aircraft used onboard Stratovision to broadcast pre-recorded courses to schools in Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin. The 200-mile radius of the broadcast was estimated to cover 5 million students in 13,000 schools, though only about 1,800 schools became paying members.

With seed money from the Ford Foundation, it sparked hope that the MPATI program, which predated widespread cable or satellite TV, would serve as a model for how educators could use the cutting-edge technology of the day to make top-flight education more accessible to students in rural America. The experiment lasted for eight years until the two-plane fleet was permanently grounded due to financial difficulties and, ironically, a National Association of Educational Broadcasters study that argued MPATI used too much of the UHF television spectrum.

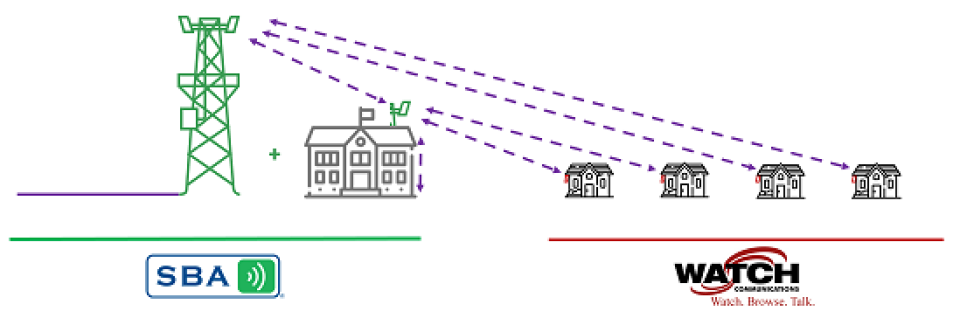

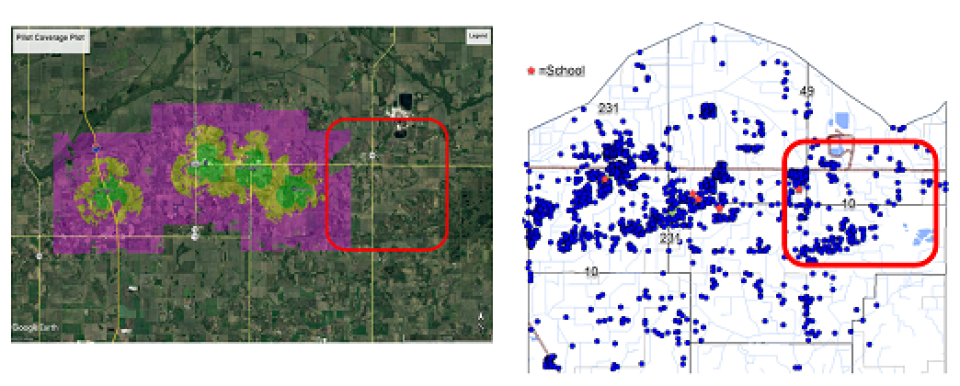

Today, the Purdue Research Foundation's Innovation Partners Institute (IPI) has resurrected the spirit that gave wings to MPATI in an effort to reach students in the Kankakee Valley School Corporation with a pilot program of a different sort. Instead of using Stratovision and airplanes, IPI has partnered with Wabash College, SBA Communications, Watch Communications, and the State of Indiana to connect 500 households to a wireless broadband network in support of remote learning.

“I was tasked with leading the ‘Safe Campus’ initiative at Purdue (University) when Covid hit, which accelerated the potential of adapting new technology. What we realized is that when it comes to learning, especially in rural areas of Indiana, one in four students don’t have connectivity,” said David Broecker, Chief Innovation and Collaboration Officer at the Purdue Research Foundation, which manages Purdue’s Discovery Park District.

The IPI looks “for challenging community problems and then aims to assemble an A-list of academic and corporate partners with the exact skills, experiences, and capabilities to collaboratively bring novel solutions forward.” “Because of the institute’s virtual nature,” its mission statement continues, “these experts function as ‘innovators in network’ as opposed to ‘entrepreneurs in residence’ who tap their own networks and partners to develop solutions.”

The E-Learning pilot project for the Kankakee Valley School Corporation is IPI’s first initiative.

“We realized we could quickly pivot (to address the digital divide), Broecker explained. “Technology should not be a bottleneck.”

To lead the project, IPI enlisted Mohammad Shakouri, Director of Community Broadband Initiatives at Joint Venture Silicon Valley and CEO of Microsanj.

Leveraging Existing Infrastructure To Build A Private Network

Shakouri, whose brother is a Professor of electrical engineering at Purdue, said they targeted the Kankakee Valley School Corporation because its five schools, which serve approximately 3,400 students in grades K-12, had an existing fiber connection for internal use they could leverage in conjunction with existing infrastructure owned by SBA Communications.

“This is a wide area network that would normally take years to put up. We were able to do it in months with quick approval from the county,” Shakouri said.

That means the channel will provide between 200 and 300 Megabits per second (Mbps) upload and download speeds to be shared across households. At the beginning of the new year, engineers will install access points at each of the designated households, which will allow those households to connect via home Wi-Fi.

“It’s not an open network. It’s completely connected to the school network and optimized for e-learning,” Shakouri explained, noting how they are currently testing Zoom applications to ensure the network will be able to provide enough bandwidth to meet the connectivity needs of what amounts to 1.5 to 2 students per household.

“What makes this unique is that we leverage existing infrastructure with new spectrum to develop a private e-learning network,” Broecker added.

It all comes at an estimated price tag of $1 million with philanthropic funding from Jay and Robyn Stead of Auckland, New Zealand. The sizeable donation from Jay Stead, a Purdue University graduate, was pooled with money from the Indiana Governors Emergency Educational Relief (GEER) Fund and other private donations to shoulder the costs.

“The goal,” Brocker said, is to “get it up quickly, show what’s possible, and extend the network to other school systems. We chose Kankakee first because of the existing infrastructure and because the school system willing to work with us.”

School officials are anxious for the network to be fully-operational, which is expected to happen in January of 2021.

“This project will help us overcome the lack of connectivity in our area that suddenly became a huge hurdle for many of our students when we moved to e-learning in the spring,” said Don Street, Superintendent of the Kankakee Valley School Corporation.

While there are no other school districts lined up to connect yet, Shakouri said they have identified 10 other counties in rural Indiana that would make for good candidates should the pilot project in Kankakee Valley prove successful.

More Schools Turn To CBRS

The approach IPI is taking in Indiana is similar to what is happening with the Patterson Joint Unified School District in California. Patterson draws students from eastern Santa Clara County and western Stanislaus County, where more than 70% of the student body is considered low-income, many of whom live in households that can’t afford to pay for Internet access.

The Patterson School District opted to engage “Motorola Solutions’ Nitro private wireless network, installing CBRS radios and antennas at all eight schools in the district with help from Motorola partner BearCom. Two thousand families will receive Nitro modems, wireless routers, and SIM cards that they can put into district-issued Chromebooks in order to connect to the CBRS network. To date, the total cost of the project is roughly $2 million,” according to Fierce Wireless.

Utah schools are also in the process of leveraging CBRS to connect students who lack Internet access. As Campus Technology reports, the Utah Education & Telehealth Network (UETN) is working with TLC Solutions to build the core network infrastructure.

According to the New America report “The Online Learning Equity Gap,” the most ambitious of these initiatives “may be the state of Maryland's plan to develop a high-speed broadband network using 3.5 GHz unlicensed spectrum. Maryland’s CBRS network is intended not only for rural areas of the state, but also urban areas where students may live in households that cannot afford broadband.”

While a number of communities are using CBRS to build out private networks to connect students at home, some cities are pursuing different approaches, as we have highlighted in recent stories, such as the Chicago Connected initiative in Illinois that seeks to provide a high-speed connection for 100,000 students for up to four years by directly paying Internet Service Providers to deliver the service.

And then there’s the Every1online project in the Greater Pittsburgh area, which brought together the nonprofit Meta Mesh, Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Pittsburgh, two school districts, another nonprofit, and an array of local stakeholders to provide broadband access to more than 450 families for a year. There they’ve built a fixed wireless system offering free connectivity to families involved in the pilot program, which will run for the next year.

For students in Kankakee, the IPI’s E-Learning initiative will be in place for two years. However, Shakouri said, “we want this to be sustainable for the long run. We need to solve problem for the long run.”

Better Policy Is Needed

Indeed, solving the “problem for the long-run” is vital. And part of the long-run solution will need to include how connectivity challenges extend beyond remote learning.

While school districts across the country are being forced to address the digital divide challenge on-the-fly, the failure of local, state, and federal government policy-makers to systematically address the lack of reliable, affordable and truly high-speed Internet access for millions of Americans is glaring one. Ensuring that all school students have Internet connectivity is essential, but what we are seeing are solutions that are focused exclusively on schools in many communities. What these school-focused initiatives understandably exclude are the millions of people without children but who still need Internet access.

One approach to addressing the digital divide more broadly can be found in Providence, R.I., where the Rhode Island-based nonprofit One Neighborhood Builders (ONB) is building a free community wireless network in the Olneyville neighborhood in west-central Providence.

ONB focused their efforts on the Olneyville neighborhood through a healthcare lens because it was a part of the city where, as Covid-19 cases surged among low-income residents, neighborhood residents were left with fewer options to get online to work, visit the doctor, and shop for groceries.

In explaining the impetus for building a community wireless network, ONB Executive Director Jennifer Hawkins said the pandemic is a “striking reminder of how important a social and economic determinant of health” Internet access can be. It’s “[s]omething pre-pandemic we would have considered an inconvenience,” but which, Hawkins added, “has become this meta issue when it is crucial to live, to learn, to work, [and] to connect with family members.”