Marin County and the city of San Rafael, California, are demonstrating what happens when local government, a community nonprofit, and generous stakeholders come together to do something right. Over the summer they’ve built a Wi-Fi mesh network in the city’s Canal neighborhood to connect over 2,000 students and their families in anticipation of the upcoming school year. How the project unfolded shows what a thoughtful, committed group of people can do to respond to a public health crisis, close the digital divide, and make a long-term commitment to the vulnerable communities around them.

A Neighborhood in Need

The Canal neighborhood (pop. 12,000) was founded in the 1950s and sits in the southeast corner of Marin County, bounded by the San Francisco Bay to the east, the city of San Quentin to the south, China Camp State Park to the north, and the Mount Tamalpais Watershed to the west. It’s split down the middle by Highway 101 and Interstate 580.

Canal is populated by predominantly low-income workers, and remains one of the most densely settled areas in Marin County — one of the wealthiest counties in the nation. Its residents serve, according to San Rafael Director of Digital Services and Open Government Rebecca Woodbury, as the backbone of the area’s service economy. Those who live there are mostly Latinx residents, with a small but significant segment who identify as Vietnamese. A 2015 study highlighted the challenges the community faces. Its population grew by half between 1990 and 2013, while available housing units grew by just 15%. During the same period, median household income shrunk by nearly a third, and unemployment remains twice as high in Canal than in the rest of Marin. It suffers from the largest education disparity in the entire state. It’s also among the hardest hit in the community by the coronavirus pandemic: the Latinx population in Canal accounts for just 16% of Marin County but 71% of cases so far.

Canal neighborhood residents are also among the least connected in the county. A recent survey by local nonprofit Canal Alliance showed that 57% of residents don’t own a computer, compared to just 10% of those who live outside the neighborhood. 44% reported that it was difficult to connect to the Internet, and 42% responded that their connection was not fast enough to watch a video without it buffering within the first ten seconds.

When the public health crisis hit and students were sent home in the spring, city, county, and school officials went into high gear to solve the connectivity crisis. The timeline gave them little opportunity to prepare, and they were so hard-pressed to get as many connected as quickly as possible that there wasn’t time for a lot of strategic planning, said Rebecca Woodbury in an interview. The city and school bought hotspots, distributed Chromebooks, and helped get families connected to Comcast’s Internet Essentials, but bottlenecks and backlogs slowed the process every step of the way.

When the pandemic first hit, what we were really trying to solve for was when school moved to the remote model, we were just looking for what can we do the fastest to solve this problem. It’s heartbreaking because it’s a crisis of poverty more than anything else. —Rebecca Woodbury, San Rafael Director of Digital Services and Open Government

Coming Together

Then, in late spring, Rebecca was contacted by Lionel Florit, a community member working for Cisco Systems (who was willing to pay him for ten days of community volunteer work) who said a Wi-Fi mesh network could be built relatively quickly and efficiently to get residents in the Canal neighborhood connected. “I reached out to the county and they said yes before I even finished my sentence. It was so cool. It really snowballed,” Rebecca remembered. Very quickly a team came together, including Lionel, David Cooper (chief engineer of a private company called Marin IT who also volunteered his time), San Rafael City Schools Chief Technology Officer Sarah Ashton, and Marin County’s Chief Assistant Director Javier Trujillo. San Rafael’s Data and Infrastructure Manager led the team, and the Canal Alliance joined the coalition early — as a long-time, trusted local nonprofit providing a host of services with deep community ties, it played a pivotal role in collecting information, planning, and executing the network.

Pivotal to the effort was the financial commitment made by the county, local nonprofits, and philanthropists. Marin County contributed $75,000, the Marin Community Foundation contributed $125,000, and the Pincus foundation gave $125,000 as the project unfolded, which pushed it beyond its fundraising goals.

Data collecting and mapping were key early on in the process, and the group set about finding where the most densely population portions of the neighborhood were so that they could reach the largest number of people as quickly as possible. The next step was inventorying assets for access point placement and reaching agreements with Marin General Services Agency, the entity that managed the city streetlights. Through Dave Cooper, Cisco hardware was purchased at a discount, and additional Aruba hardware was donated. Clearpath serves as the network services platform, with Cisco Umbrella being used for basic filtering services. Ultimately, around 20 antennas have been placed — including on a community center, on government buildings, on two pump stations, on Canal Alliance-owned residential buildings, and on street poles.

The San Rafael Mesh Network

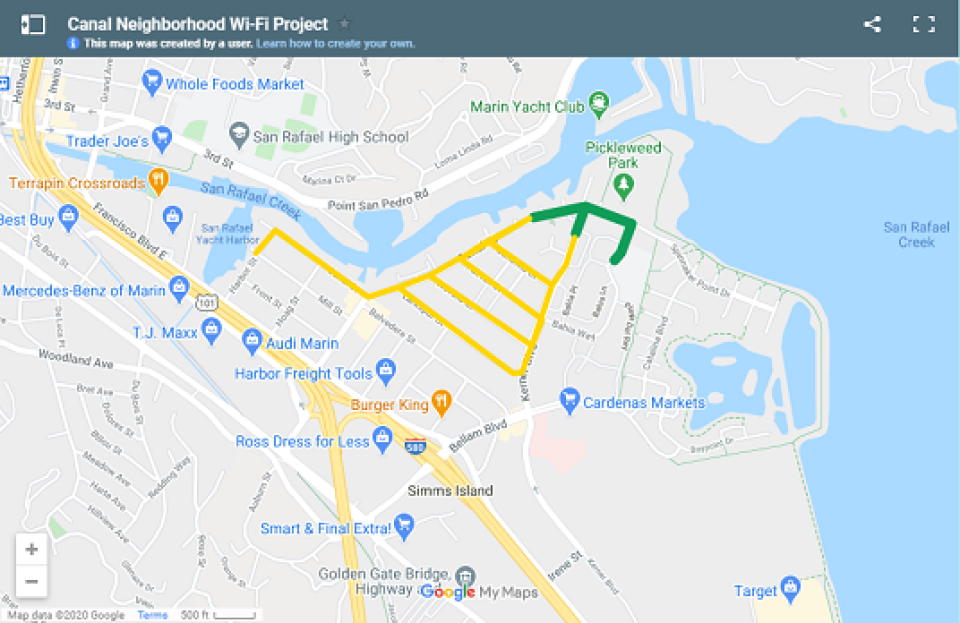

Initial parts of the network launched on August 31st (below, in green). It’s currently in something of a public beta, as the coalition works to ensure that it meets community needs and can handle expected traffic loads. More portions will come online in the coming two weeks (below, in yellow). Students can connect via the Chromebooks handed out by their schools, and community members can do the same via their home devices and smartphones. The access portal is a dynamic landing page that includes information for students as the school year begins, but also community news and resources related to food security, eviction protection, and mental health and wellness.

Hardware costs ran $190,000, with projected ongoing costs of $55,000. According to Rebecca Woodbury, the network was also designed with the state’s perennial fire season problems in mind. The county endured a multi-day brownout in 2019 as PG&E preemptively shut off power to prevent further ignition events along its aged and poorly maintained infrastructure. Tens of thousands were without power, and while many wealthy residents left San Rafael to stay in hotels across the bay, Canal residents were stuck in place without power or connection to the outside world. City officials were forced to go out and tape handmade banners with news and updates to government buildings to get information out. For the new mesh network, the tentative plan is to put generators by access points on the pump stations, government building, and community center, so that even if the whole network cannot be kept online in the event of another brownout a core area will remain.

The network and its hardware is owned and administrated by the Marin Information and Data Access Systems’ institutional network, called MIDAS, which connects municipal and community buildings throughout the county.

With the hardware placed, efforts have turned to getting people connected. The stakeholders behind the project have had to take into consideration unique obstacles, including the fact that English isn’t the predominant language [pdf] in the neighborhood. There are, in addition, basic literacy challenges which make posting instructions about how to connect more difficult. And the coalition behind the project is acutely aware that they are building a public network in a community where many are suspicious of giving out information to the government, which is why the presence of the Canal Alliance and other trusted community stakeholders is so important. Engendering trust to use it is just half the picture; the other is making the network and resources posted on the landing page work the first time, and including tools and information that are relevant to residents and their needs.

At present outreach includes posted information on government buildings and A-frames scattered throughout the neighborhood, with plans to augment efforts via text messages and WhatsApp. The coalition is also in the process of producing video using Spanish targeted at different achievement levels and pictorial instructions to aid the effort.

Much More Than Wi-Fi

Local officials, educators, and the Canal Alliance has known for a long time that a lack of broadband was just one of the obstacles confronting neighborhood residents. On the landing page for the network is one question: how do you use it? The team is actively collecting responses so that they can adjust moving forward. And so what started as an effort to get school children connected in the middle of a pandemic has evolved into a much more rounded effort to meet community needs.

[Students'] academic gains are not just tied to having a computer. They need a roof over their head, they and their parents need to be healthy. You need to envison the entire family unit to have long-term success. —Air Gallegos, Canal Alliance Director of Education & Career

The Canal Alliance provides a host of services to residents in the neighborhood, including but not limited to adult education, student education, social services, and immigration assistance. The plan is to integrate the mesh network with those efforts to achieve better gains for all. Its will be particularly important given the number of people whose sole connection to the Internet is via their mobile device.

Looking Ahead

There are certainly obstacles to be worked out in the coming months and years. Early residential development in the neighborhood means that the multi-dwelling units (MDUs) tend to have courtyards, which makes those with apartments facing inward unable to achieve strong connections from access points placed on street poles. Phase two of the plan will include working with property owners to install hardware inside of buildings to reach these residents.

“I’ve been reflecting a lot on it,” Rebecca said of the project. “It feels like we’re living in a world where everything is not working, and this project has worked. I think it was the right people. This project is really a testament to cross-agency, cross-sector cooperation. If everything in government worked like this, we would have fewer problems.”

In the future, the group is looking at options to connect to CENIC (Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California), another a nonprofit institutional network which has strong backhaul support to provide more and faster simultaneous connections.

It was a process that taught the coalition a lot, and because the group got more equipment than they needed, a mesh network for Marin City, a densely population area with a lot of public housing, is in the pipeline. Distant plans also include a wireline broadband network in the Canal neighborhood, though it’s still early.

We still want to strive for everybody having an affordable, reliable Internet connection. That’s the dream. —Rebecca Woodbury, San Rafael Director of Digital Services and Open Government

For more, listen to Christopher talk with Rebecca and Air in Episode 427 of the Community Broadband Bits podcast.

Header image via Wikimedia Commons from Robert Campbell, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Digital Visual Library