Schools offer not only education, but nourishment, a place to form friendships and bonds, and a way to make sure youth are safe. When the pandemic hit, schools had to transition to distance learning and, as a result, many students disappeared because their family didn’t have access to or couldn’t afford a home Internet connection. It became immediately clear, all over the country, that a lack of broadband access and broadband affordability were no longer issues that could be ignored.

Many cities throughout the U.S. have been working over the last year to address this issue, but one city in particular - Columbus, Ohio - has been taking a holistic approach to broadband access.

The Franklin County Digital Equity Coalition was borne out of the emergency needs presented by the pandemic, but has shaped up to be a good model for how to address the broadband issues facing urban communities across the country.

After 11 months of meeting and planning, the coalition released a framework in March outlining its five pillars of focus: broadband affordability, device access, digital life skills and technical support, community response and collaboration, and advocacy for broadband funding and policy.

The coalition also developed two pilot programs to increase broadband access.

The first, which was a quickly deployed and desperately needed response to the lack of broadband access, was the Central Ohio Broadband Access Pilot Program. Launched in September 2020 in anticipation of the upcoming school year, it offered hotspot devices with unlimited data plans to central Ohio households with k-12 students. The program, while still growing, has been deployed with about 2,300 hotspots distributed so far with the help of PCs for People.

The second (the City of Columbus and Smart Columbus Pilot Projects) uses the city’s existing fiber backbone to bring affordable Internet service to the Near East and South Side neighborhoods in Columbus.

Both pilot programs are the result of nearly 30 organizations coming together to get affordable access to some of the city and county’s most vulnerable populations.

There’s Power in Numbers

Every year, the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission (MORPC) puts on an event called the “State of the Region,” in which local officials, state politicians, business, and civic leaders attend and hear about progress and plans that have been made to address issues in the region.

At the 2017 State of the Region, Aaron Schill, MORPC Director of Data and Mapping was sandwiched between Angela Seifer, Executive Director at the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, and Anne Schwieger, Broadband and Digital Equity Advocate for the City of Boston. The main topic of the event that year: broadband and digital equity.

“This is not something we are new to. It’s something that over the past several years has been a growing concern in the community,” Schill told us in an interview. “We were having more conversations with folks in the community - informal conversations - just trying to get a sense of who was doing what in the digital equity space.”

MORPC has more than 70 members which include counties, cities, villages, townships, and regional organizations. MORPC has been working with its members on broadband solutions for years, but when the pandemic hit, everything changed.

“What had been focused on coalition-building and networking, our work, and my work in particular, quickly transitioned to emergency response,” Schill said.

The Columbus Metropolitan Library, a central institution in the City of Columbus, had to close its doors in March 2020, cutting people off from access to free Wi-Fi for virtual learning, applying for jobs, finding housing and seeking other social services.

It was incredibly disruptive, but it pushed the organization and several others in Franklin County (including MORPC) to try to find immediate solutions. A handful of leaders from organizations across the region started getting together weekly, but eventually the meetings grew to include nearly 30 organizations. The group organized to become the Franklin County Digital Equity Coalition.

“It’s a matter of people being able to fully participate in society, and without Internet access people can’t do that from an economic perspective, because it’s critical to job access, medical and wellness because of telehealth these days,” said Nikki Scarpitti, Director of Strategic Initiatives and Advocacy at the Columbus Metropolitan Library. “We feel that by helping the most vulnerable participate fully in society that it’s going to essentially help everyone.”

For the coalition, honing in on the strategies to address the challenges facing the city of Columbus was also driven by the results from two additional studies.

The first was a June 2020 study funded by the Columbus Foundation and conducted by AECOM. The study assessed the current state of broadband access in Columbus and presented possible short-, medium-, and long-term solutions.

The second was a research initiative which included canvassing neighborhoods “to better understand how low-income residents access the Internet, and co-design solutions that could reduce barriers to digital access,” Jennifer Fening, Director of Marketing and Communications with Smart Columbus, told us in an interview.

She elaborated that one of the deliverables was a tool for helping residents understand their connectivity options and methods for assessing whether or not Internet Service Provider (ISP) were meeting subscribers’ needs. The Digital Equity Coalition is working to build these prototypes into ongoing tools on its website.

“It’s funny because many people who want to help assume there is not digital literacy, but these people are super deft,” Fening said.

Why These Two Neighborhoods?

When Smart Columbus - a organization that is part of the steering committee for the coalition a smart city initiative and a partner in the neighborhood pilot project - was trying to identify neighborhoods for the pilot program, they started by mapping data from Columbus Public Schools on disengagement of students during the spring of 2020.

“[We were identifying] what kids were not logging onto the distanced learning when they made the switch, from the March to May timeframe. There are just students who weren’t heard from again,” Fening said.

While students not signing into class could be the result of a number of factors, the coalition thought providing affordable broadband could eliminate one of the challenges many students faced. They ended up overlaying that map with the city’s fiber assets and the locations of public buildings that would be suitable for installing the radios for each network.

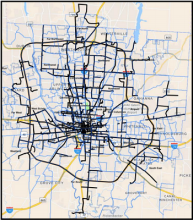

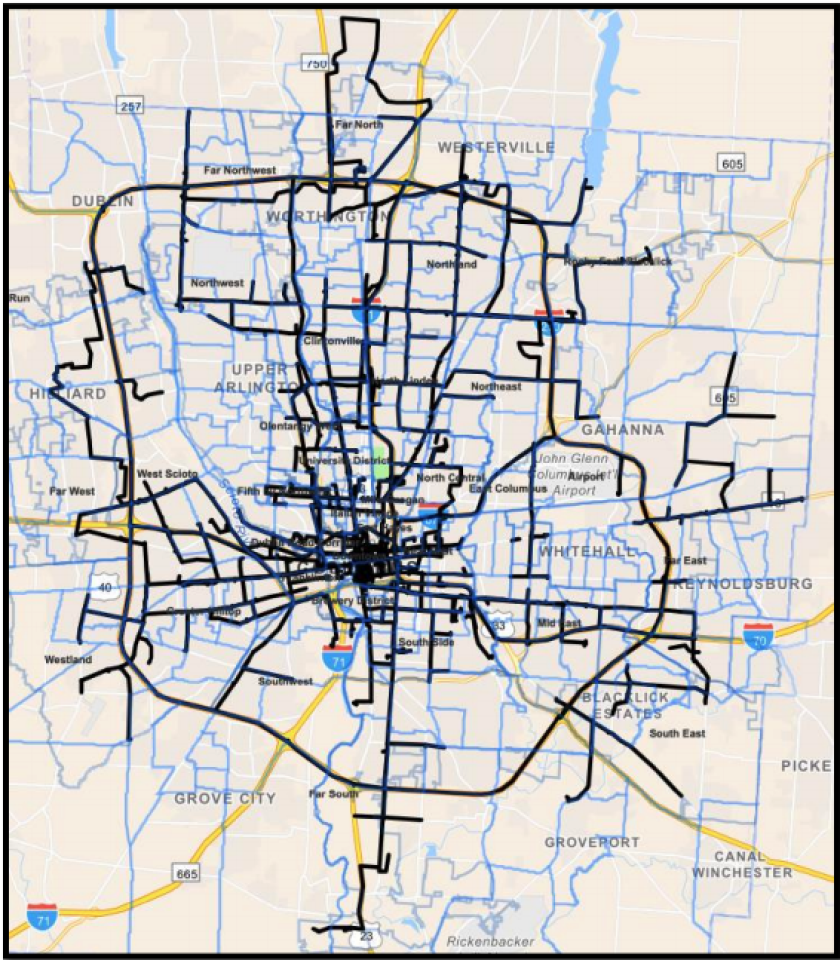

The city’s fiber network (see left) runs more than 1,000 miles and consists of 288 strands connecting city facilities and transportation infrastructure, with a smaller portion reserved for a commercial dark fiber network. The city projects it will continue to invest $2 million to $2.5 million annually in the network.

Both neighborhoods are predominantly communities of color that have lower income and lower employment rates and have overall been cut off from opportunities, Fening said.

In the framework, the coalition lays out some pretty stark statistics.

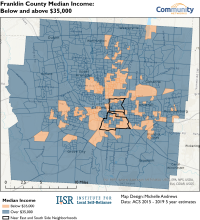

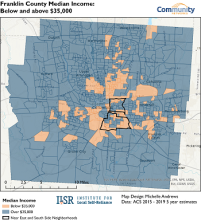

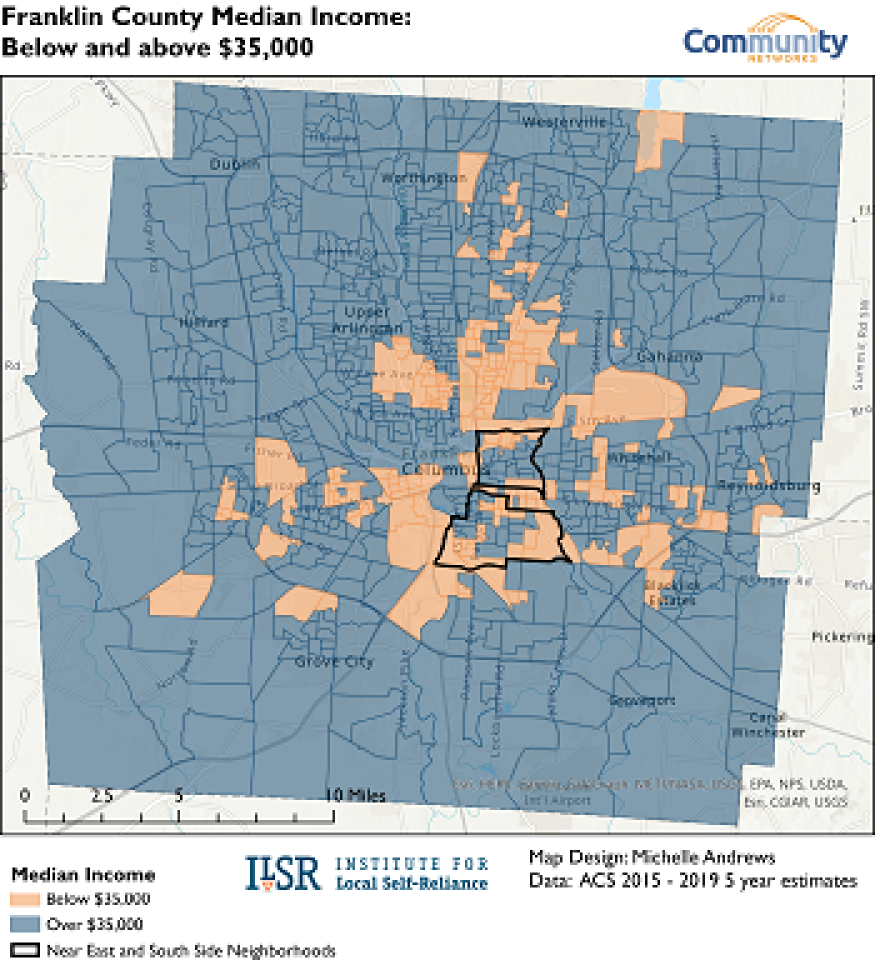

In Franklin County in 2019, 1 in 5 households did not have a cable modem, DSL or fiber accounts. Ten percent of households could only access the Internet through cellular data plans. Nine percent of households had no option for accessing the Internet. Households with income below $35,000 accounted for 70 percent of those with no Internet subscriptions in Franklin County.

ILSR’s analysis of the U.S. Census American Community Survey data 2015-2019 found that across Franklin County, there were racial disparities in homes with computers but no Internet subscriptions. We found 4 percent of white residents and 2.1 percent of Asian residents reported not having an Internet subscription, while 9 percent of Black, 9 percent of Hispanic/Latinx, and 9 percent of American Indian and Native Alaskan households do not have subscriptions. Households that identified as being two or more races or a race that was not listed in the survey reported at rates of 5 percent and 17 percent, respectively.

When we looked at the same data for the Near East and South Side Neighborhoods (the two targets for the pilot project), nearly all of the numbers jumped: 6 percent of White, 13 percent of Black and 15 percent of Hispanic/Latinx households reported not having an Internet subscription, with households identifying as being two or more races or a race that was not listed in the survey reporting rates of 6 and 19 percent, respectively.

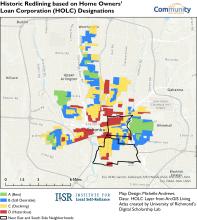

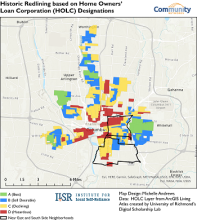

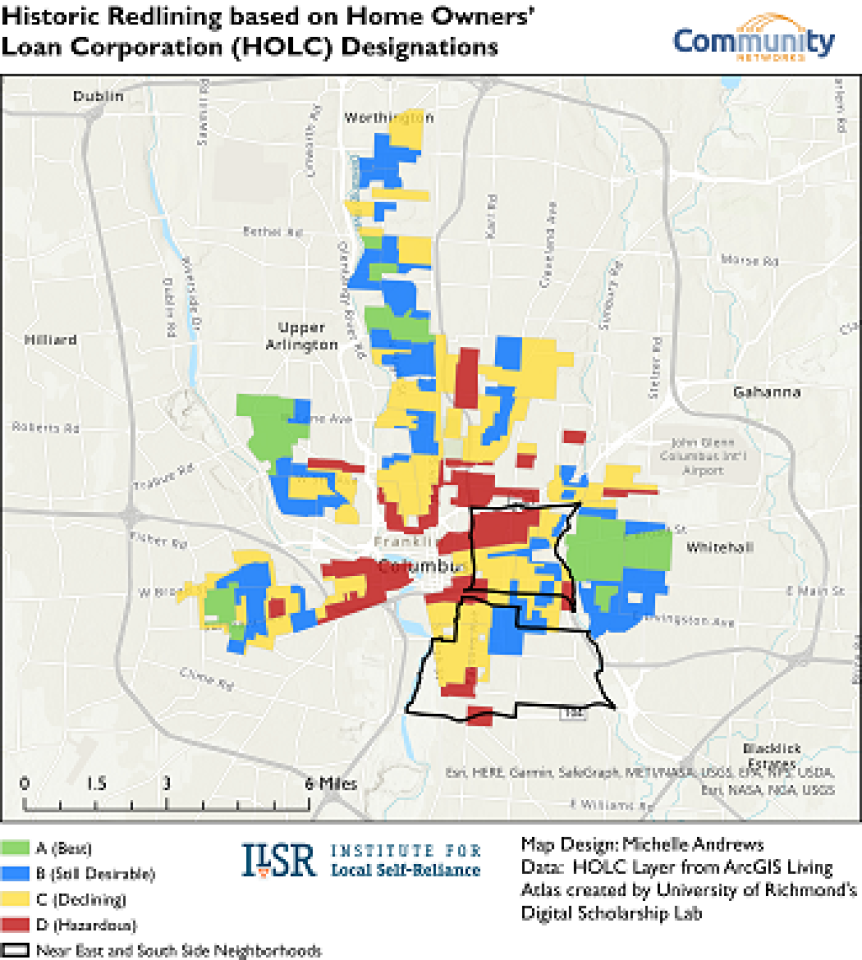

The coalition also cites a report by Free Press in 2016, which points out that a lot of the disparities in adoption between racial demographics comes from systemic racial discrimination across multiple industries, often connected to redlining.

Redlining came about in the 1930s as one of the consequences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which in an effort to help solve the housing crisis for white Americans left Black Americans without access to home loans, deemed predominantly Black neighborhoods as too risky for insured mortgages, and forced segregation. Redlining has led to communities of color missing out on access to one of the most common avenues for achieving trans-generational wealth in this country: homeownership (for an enlightening look at this history, check out The Color of Money by Mehrsa Baradaran.) Such trends continued into the 1960s with the advent of the federal highway system, and placed additional obstacles in the way of those who are Black, Indigenous or People of Color (BIPOC).

I-70, which runs through the heart of Columbus, just so happens to split the two pilot project neighborhoods identified as having among the greatest need down the middle.

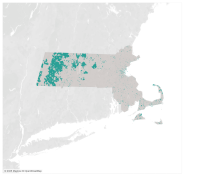

ILSR analyzed historical redlining data in the city (see map, right. For a high-resolution version, click here) and found both of the neighborhoods selected for the pilot program had swaths of the community which were given C or D grades and deemed “Declining” or “Hazardous” back in the 1930s because the neighborhoods were working-class with either first- or second-generation immigrants and a high population of Hispanic/Latinx and Black residents.

Our analysis found the median income in Franklin County is $61,000, while in the Near East and South Side Neighborhoods it’s $36,000 (see map, right. For a high-resolution version, click here). With the cost of the average broadband connection on the rise across the country, the decision to subscribe is far more difficult for families with lower incomes that also have to consider the cost of rent, groceries, health insurance, child care, and a host of other monthly expenses.

The bottom line is that if students in these neighborhoods aren’t logging into class, it’s not

A Test Run

Once the neighborhoods were identified for the City of Columbus and Smart Columbus Pilot Project, the coalition put out an RFP using CARES Act funding to identify a last-mile service provider. The requirements were 50 Mbps (Megabit per second) download speeds at $15/month, and serving about 100 households per neighborhood. Schill said there were seven to nine respondents proposing five different technologies.

The coalition decided on two proposals. For the Near East neighborhood, Starry, a Boston-based fixed wireless ISP, will provide millimeter-wave service using one radio fixed atop a building and antennas throughout homes in the neighborhood. Motorola will serve the South Side neighborhood using a new last-mile wireless approach utilizing CBRS (Citizen Broadband Radio Service) and modems installed in households.

While the initial RFP had 100 households per neighborhood, Motorola will ultimately be able to serve 300, and Starry will be able to serve 400 households. Both networks will use the city’s backbone fiber, which Schill said is one of more extensive institutional networks in the country.

To be eligible to participate in the program, residents in the neighborhoods must be participating in distance learning in their homes. Smart Columbus’ description of distance learning doesn’t just include k-12 students, it also includes individuals working on their GED, attending college classes, and taking advantage of any other workforce development opportunities.

There are some challenges with both networks getting households online. With the Motorola network, the two-step process of distributing the modems and then educating people on how to install the devices themselves could prove to be a challenge. With Starry, there will be appointments for antenna installations, which means if residents do not own their home, they will have to get written consent from their landlords.

While user enrollment is underway for the Motorola network, the Starry network is working on infrastructure deployment. Both networks will offer a $50 grocery gift card incentive which will be given out after installation.

While these programs are both temporary, the coalition has stated in its framework that if the networks are successful they will hopefully show policymakers, funders, and existing ISPs that the affordability issue can be addressed with these new models affordable broadband service for low-income residents.

“[It’s] a way to, not just open up service in a couple of neighborhoods, but also test the scalability of a couple different technologies to see what might work on a broader scale,” Schill said.

Smart Columbus is hoping to have the Starry infrastructure operational for resident use by the end of May.

The coalition is the first of its kind in many ways. The structure of the coalition has the Steering Committee, made up of 10 organizations (including the Columbus Metropolitan Library, MORPC and Smart Columbus) at the helm. The members of the steering committee all focus on one of the four initiatives: broadband affordability and access, device access, digital life skills and advocacy. All of the initiatives have their own working group.

The coalition is also being thoughtful about how they are involving the ISPs. Part of what’s made the Franklin County coalition such a grassroots movement is that the ISPs are not formal coalition members. When states have created task forces and committees, they have often had many ISPs as members, which has allowed them to set the agenda and rendered many of the efforts relatively ineffective. However, the Franklin County Digital Equity Coalition’s steering committee is holding regular meetings with the ISPs in order to find ways to collaborate and partner around digital equity efforts. The coalition seeks advice and partnership from ISPs, but continues to keep its stakeholders' and communities' needs central to its vision.

“It’s a fine political line to walk, but at the end of the day we do want to partner with them,” Scarpitti said. “They also have different interests and intentions than we do in terms of how we serve the most vulnerable in the community.”

The coalition is hoping that this strong push for more access and affordability to broadband and digital skills will make tomorrow better for the residents of its county.

Special thanks to ILSR Data and Visualization Researcher Michelle Andrews for her work on demographics and redlining, and providing the related maps above.

For timely updates, follow Christopher Mitchell or MuniNetworks on Twitter and sign up to get the Community Broadband weekly update.