A new report out by CTC Technology and Energy and Rural Innovation Strategies, commissioned by the state of Vermont, gives us one of the clearest and most detailed pictures so far of the impact of the Covid 19 pandemic on our attempts to live and work remotely.

The “Covid-19 Responses Telecommunications Recovery Plan” [pdf], presented to the state in December 2020, includes both a comprehensive survey of conditions after a half-year of social distancing and intermittent lockdowns as well as recommendations for addressing immediate needs. But it offers solutions that provide a path forward by making sure that dollars spent now are in service to the state’s long-term goals of getting everyone in the Green Mountain State on fast, affordable wireline broadband service at speeds of at least 100/100 Megabits per second (Mbps).

The report brings together network performance assessments from every level of government across the state over the last six months, pairs it with survey responses from citizens, libraries, hospitals, businesses, regional development corporations, and Communications Union Districts (CUDs), and offers analysis based on conditions for moving forward.

“Covid-19 has laid bare the challenges of lack of universal broadband in Vermont,” the report says, with “inequities in the availability and affordability of broadband create further inequities in areas such as education, telehealth, and the ability to work from home.” It offers a wealth of findings:

- Broadband use has increased dramatically since the start of the pandemic, as would be expected. For example, respondents to an online poll report increased use of the Internet for telemedicine (an increase from 19 percent to 75 percent) and for civic engagement (an increase from 33 percent to 74 percent). Additionally, 62 percent of respondents use the Internet for teleworking on a daily basis, compared with 21 percent of respondents before the pandemic.

- Overall, satisfaction with Internet service aspects has decreased during the pandemic, particularly for speed and reliability of service. More than one-half of respondents are not at all satisfied (approximately one-third) or are only slightly satisfied (approximately one-fifth) with connection speed and reliability during the pandemic.

- Many municipalities have struggled to engage citizens and elected officials via online tools, and few have made plans for larger engagement challenges like Town Meeting Day.

- Low-income Vermonters in particular are facing challenges accessing broadband and getting assistance.

- Small businesses, remote workers, parents, patients, and civically engaged Vermonters are learning digital skills quickly, but are still struggling to understand how to use connectivity tools during the pandemic.

See the full report for the list of findings [pdf].

To remedy this and position stakeholders across the state for future success, it offers three overarching recommendations:

- Provide a Broadband Service Subsidy to Low-Income Vermonters During the Pandemic

- Fund Modest Infrastructure Enhancements Where Feasible in the Short-Run and in Areas Where These Investments Will Not Compromise Long-Term Efforts

- Develop a Broadband Corps

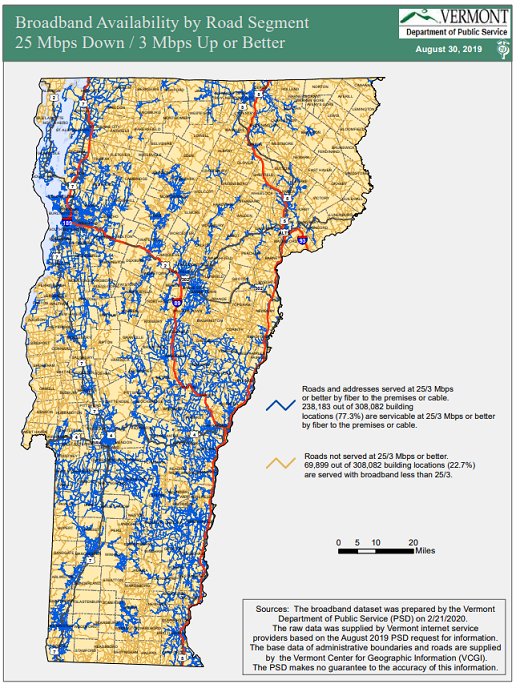

The report outlines the cost for the above recommendations to reach the roughly 61,000 households that lack service of at least 25/3 Mbps. The first of these problems tackles the persistent challenge (not only in Vermont but across the country) of getting qualifying low-income households on existing private ISP programs like Comcast’s Internet Essentials and Charter Spectrum:

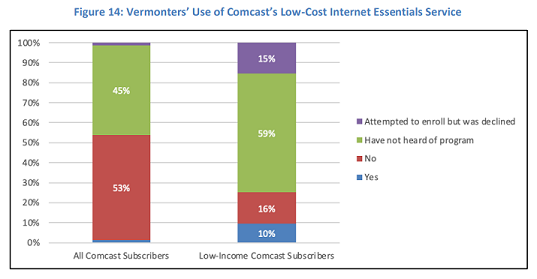

Only one percent of all Comcast subscribers, and 10 percent of low-income subscribers, participate in the Comcast Internet Essentials program. Another 59 percent of low-income subscribers were unaware of the program, and 15 percent attempted to enroll but were declined.

A statewide program with fewer barriers to entry and a stronger outreach arm, it argues, would assist a great many in a short period of time. The subsidy program would include $30/month for 20,000 households and cost $7 million over 12 months.

Infrastructure-wise, the bulk of poorly connected residents can be reached, the report says, by making use of existing mobile networks and distributing hotspots to 45,000 households (and rooftop boosters for 3,800 more in areas where mobile reception is weak). Another 1,700 unserved home close to existing private-provider infrastructure (and thus unlikely to become a part of future CUDs) could be connected with additional cable or fiber service at the cost of $4.5 million.

Mobilizing a Broadband Corps

The last recommendation made is that Vermont establish a statewide Broadband Corps program which would initially dedicate itself to “mobilizing the people power necessary to confirm mobile hotspot options, assist with nontechnical installations, and provide technical assistance for low income and technology-challenged Vermonters.” Similar to the National Digital Inclusion Alliance’s new Digital Navigators initiative, the Broadband Corp would assist communities in bringing together local residents to help their neighbors with skills challenges or a lack of familiarity get and stay online.

“Small businesses, remote workers, parents, patients, and civically engaged Vermonters” the report says at the outset, “are learning digital skills quickly, but are still struggling to understand how to use connectivity tools during the pandemic.” The Broadband Corps would address these problems, beginning with the new year and “continu[ing] for the next 8-10 months.”

This is where the report envisions this Broadband Corps as something more. After the pandemic subsides, it suggests that these volunteers transition “to longer-term data collection (such as pole assessments) in the late spring once emergency connections are completed.” The report’s explanation of the work thereafter is worth quoting at length:

We recommend the creation of a Broadband Corps in order to: (1) Assist with infrastructure and service deployment; (2) Perform outreach, and direct technical support to Vermonters becoming familiar with their broadband connections and devices; and (3) Provide high touch support to ensure low-income Vermonters take advantage of broadband support programs.

If the Corps is successful in connecting Vermonters rapidly, we recommend in the spring that Corps members spend available time on pole surveys of towns on behalf of CUDs and thereby advance their work toward deploying fiber.

As an illustration of what is possible, this Report describes a Broadband Corps structure that combines regionally assigned Corps members with a statewide installation team. Corps members could be assigned to Regional Planning Commission regions and could work closely with RPCs and/or CUDs if desired, with centralized, statewide management. We recommend at least 22 regional corps members (two for each RPC region), and at least 20 statewide Corps members. While a Corps could be put together quickly to get started as early as December, it is likely such a team would be focused on executing for a six-month period, for a budget of approximately $1.3 million, including staffing and equipment.

This is a significant reimagining of the model, and one that would be exciting to see mobilized. It also stands at the heart of the report’s framing of the problem of Internet access in Vermont writ large: that the future of expanding broadband and building better networks rests with the locally owned, controlled, and operated CUDs which have been gaining momentum since state law change two years ago. “Ensuring CUD buy-in to further short-term emergency planning,” the report says, “is essential to maintain a clear, efficient path toward universal 100/100 service in Vermont . . . [T]he work they have done during the pandemic to continue on the path to fiber networks, while also exploring short-term options, has only increased their sophistication and understanding of the challenges that lie ahead.”

Eschewing Wireless

Interestingly, the report abstains from recommending fixed wireless as a gap solution, despite the fact this has been among the most popular responses to the pandemic around the country. As justification it cites the permitting and installation process as too long to be immediately useful for Vermonters, and in addition suggests that spending state dollars on wireless infrastructure threatens its 2024 goal of 100/100 Mbps service to all, outlined in its Emergency Broadband Action Plan last May: “state financial support for the expansion of permanent infrastructure that is not cable or fiber, does not contribute to the long-term goal of 100/100 service, and indeed may impede that goal.”

In pursuit of that and in addition to the recommendations above, this new report also suggests that current and future moves also advance efforts in shared infrastructure and open access networks (citing Utah as an example), a sliding scale for pole attachment fees to incent infrastructure investment in unserved and underserved areas (citing New York as an example), and an expansion of the state’s de facto dig once policy in anticipation of space on utility poles becoming scarce over the next decade.

Read the full report here [pdf], or below.